"1920s vs 2020s"! Wall Street Godfather, ECB President, and historians engage in a heated debate: "AI, tariffs, and geopolitics" dragging the world towards "1930"?

"The current 2020s bear an astonishing resemblance to the 1920s a century ago: back then it was the technological explosion of electrification and Ford's assembly line, today it is the rapid advancement of AI; back then it was the rise of dollar hegemony, today it is the pressure on the dollar system." During the heated debates in Davos, financial giants warned that the situation of "technological prosperity + trade protection + geopolitical division" is re-emerging

Key Points Summary:

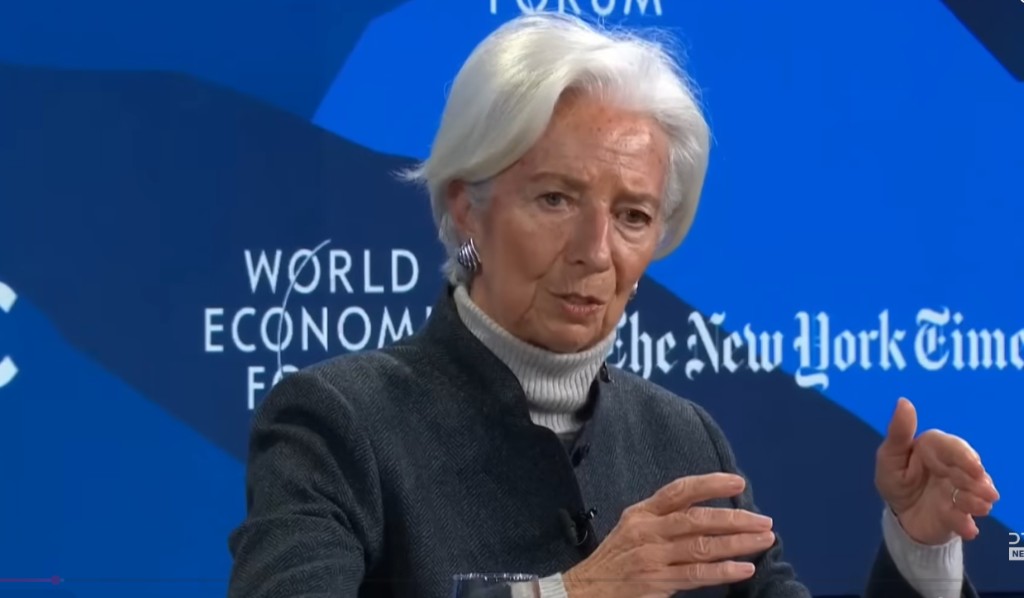

Historical Reflection: European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde and historian Adam Tooze warn that the current “technological boom + trade protection + geopolitical fragmentation” bears a striking resemblance to the path leading from the 1920s to the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Debt Crisis: Ken Griffin, founder of Citadel Securities, criticizes the “reckless spending” of governments (especially the U.S.) as the biggest threat to the current market, rather than private capital markets. “All governments are overspending, almost without exception.”

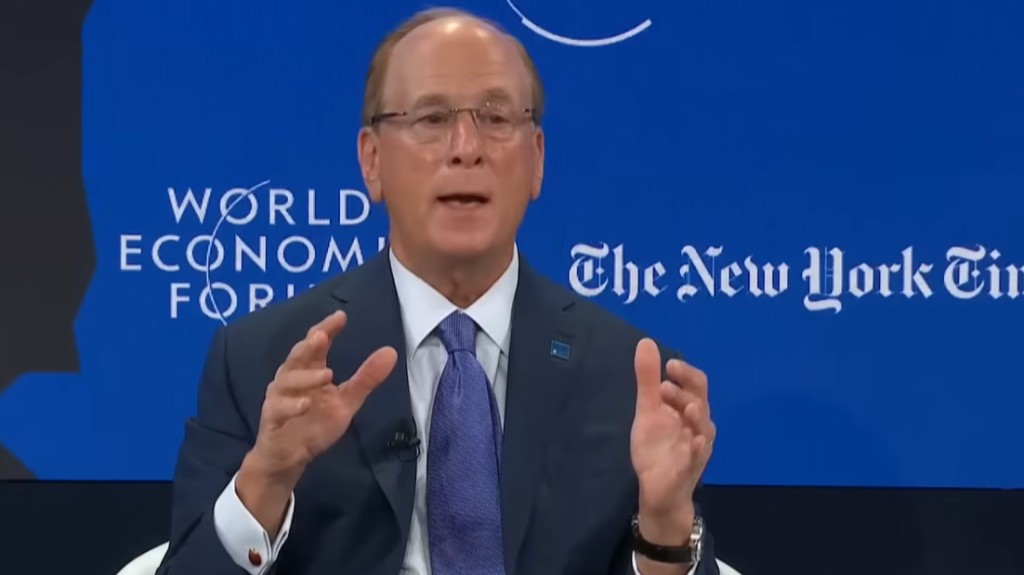

AI is Not a Bubble but K-shaped Divergence: Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock and “the Godfather of Wall Street,” believes AI is not a bubble but will lead to “winner takes all,” where giants with scale and data (like Walmart) will crush their competitors. Lagarde revealed that training a cutting-edge model requires $1 billion, and Griffin expects U.S. data center capital expenditures to reach $600 billion this year.

Tariffs and Fragmentation Threaten AI Expansion: Lagarde warns that geopolitical fragmentation and protectionism will hinder the flow of data and energy needed for AI, leading to decreased efficiency.

Cost of Tariffs: Lagarde points out that tariffs in Europe and the U.S. are rising from 2% to 15%; Griffin warns that tariffs are effectively a regressive tax on American consumers and businesses and may foster crony capitalism, stifling the vitality of small and medium-sized enterprises.

Central Bank Independence: In the face of political pressure, Lagarde reiterates the importance of central bank independence, emphasizing that fiscal consolidation cannot rely on central banks to “pick up the slack.”

Image: From left to right are Davos host Andrew, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink, Citadel Securities founder Ken Griffin, renowned economic historian Adam Tooze, and European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde.

In the cold winds of Davos, the world's top financial power figures issue a warning: uncontrolled government finances and geopolitical fragmentation may be offsetting the productivity dividends brought by AI.

In a heavyweight panel discussion the day after the 2026 World Economic Forum, Larry Fink (CEO of BlackRock, managing $14 trillion in assets), Ken Griffin (founder of Citadel Securities, managing $65 billion in assets), Christine Lagarde (President of the European Central Bank), and renowned economic historian Adam Tooze gathered together.

In this discussion, which Griffin dubbed “gloom and doom,” the guests profoundly analyzed how the explosion of AI technology, soaring sovereign debt, and geopolitical fragmentation are pushing the global economy toward a dangerous crossroads that “bears a striking resemblance to the eve of 1929”—the era that led to the Great Depression after a technological frenzy. **

Rejecting "Repeating" History, but Beware of "Rhyming"

"Mark Twain once said, history doesn't repeat itself, but it often rhymes." Columbia University historian Adam Tooze pointed directly to the core in his opening remarks. He noted the astonishing similarities between the current 2020s and the 1920s a century ago: At that time, it was the technological explosion of electrification and Ford's assembly line; today, it is the rapid advancement of AI; then, it was the rise of dollar hegemony; today, the dollar system is under pressure.

The most unsettling parallel lies in the "failure of politics." Tooze warned that in the 1920s, people tried to cover up political rifts with technology and finance, and this model of "over-reliance on money due to a lack of political imagination" ultimately led to systemic collapse.

Lagarde agreed with this perspective. She added that in the 1920s, the share of global trade in GDP plummeted from 21% to 14% within a few years, and today, although a collapse has not yet occurred, global trade is experiencing unprecedented pressure due to geopolitical fragmentation and tariff barriers. She warned that without a minimum level of global cooperation, the "scale effects" required for AI will be stifled by fragmented markets.

Fiscal "Recklessness": The Real Systemic Risk

Regarding the root of current market risks, Ken Griffin, head of Citadel Securities, provided a sharp judgment.

"This is a story about recklessness, but not the recklessness of private capital markets; it is the recklessness of government spending." Griffin bluntly pointed out that unlike the excessive leverage of the private sector in 1929, the core risk in 2026 lies in the unrestrained spending of governments. "All governments are overspending, almost without exception." He warned that this fiscal indulgence is threatening the foundations of the market.

Currently, U.S. national debt has reached $38 trillion. Griffin questioned whether Washington's hope that AI would bring significant productivity gains to "save" the deficit is realistic, as this remains uncertain. If AI does not deliver the expected productivity leap, such unrestrained spending will be unsustainable.

AI: Not a Bubble, but a Brutal "K-shaped" Cleansing

Larry Fink, who manages $14 trillion in assets, has a more micro and brutal view of AI. He clearly stated, "I don't think we are experiencing an AI bubble, but I believe there will be huge failures."

Fink introduced the concept of a "K-shaped economy." He observed that in various industries, companies with scale advantages (Scale Operators) are rapidly widening the gap with small and medium-sized enterprises through AI. He cited Walmart as an example, pointing out that its ability to utilize AI for inventory control and consumer preference analysis is far ahead.

The root of this differentiation lies in the staggering capital thresholds. Lagarde revealed on-site that the cost of developing a cutting-edge AI model has now reached $1 billion and is highly dependent on cross-border data flows. Ken Griffin provided a more macro figure: just this year, U.S. capital expenditures (Capex) for data centers will reach $600 billion—Larry Fink even interjected that "the actual number will be higher." **

Such a high "entrance ticket" means that only "scale operators" with a deep capital moat can afford to play this game. As Fink said, AI will not naturally "democratize," but may instead exacerbate the winner-takes-all situation.

Tariff Boomerang: Who is Paying the Bill?

With the recent escalation of geopolitical tensions, tariffs have become an inescapable shadow over the Davos Forum. Lagarde provided a shocking set of data: the average tariff level between the US and Europe has soared from 2% a year ago to over 12% currently, with a risk of further rising to 15%.

"If 96% of these tariffs are borne by consumers, it is certainly not good for inflation," Lagarde warned.

Griffin, from a micro-enterprise perspective, lamented the drawbacks of tariffs. He pointed out that tariffs are not only a regressive tax on consumers but also breed "crony capitalism." Under tariff barriers, companies that are closest to Washington will gain privileges, which is poison for the innovative vitality of small and medium-sized enterprises. He reminded that whether it is BlackRock, Citadel, or today's AI giants, they all started as small and medium-sized enterprises, and protecting this market vitality is crucial.

Central Bank Independence and the "Last Line of Defense"

Faced with massive debt and fiscal deficits, the market often looks to central banks to "print money to save the market" again. Lagarde took a firm stance on this, citing Paul Volcker's example, emphasizing that central banks must maintain independence and cannot become an appendage of fiscal policy.

"I do not believe that central banks will always be the 'sole savior'," Lagarde stated, noting that relying solely on monetary policy cannot solve structural fiscal imbalances.

Tooze also added that the concept of central bank independence itself was born in the 1920s to respond to populist pressures, and in the current extremely politicized environment, maintaining the central bank's "knave-proof" attributes is more critical than ever.

Full transcript of the World Economic Forum panel discussion:

Davos Host (Andrew): It is a great honor to invite these extraordinary guests to join the dialogue. Larry Fink from BlackRock, of course, he currently manages $14 trillion in assets. I should also mention that he is the co-chair of this year's World Economic Forum. You have done an outstanding job during this period.

Ken Griffin is also here. He is the founder and CEO of Citadel. He manages $65 billion in investment capital and has been at the forefront of the financial industry for decades. He has always been one of the most prescient voices regarding the direction of the economy, and we will talk to him later

Then we invited European historian Adam Tooze. He is also the director of the European Institute at Columbia University and the author of five books, including "Flood: The Great War, America, and the Reshaping of Global Order (1916-1931)."

This covers some of the periods we want to discuss. Later, Lagarde will also join us, and we look forward to discussing this issue with her. But I would like to start with Adam, if possible, please help us lay the groundwork and provide some historical context for this moment, as there are some astonishing similarities. We are experiencing an incredible prosperity. Part of it is related to technology. There were also technology-related issues at that time, followed by various monetary issues, and then tariffs that appeared later; you can start to see what that looked like.

Adam Tooze: Thank you very much. I'm really glad to be here. I do want to express my gratitude for making this Davos Forum happen in this way. It is an extraordinary experience, and it is truly an honor to be here. Yes, I would like to continue.

As you just mentioned, Andrew, I think you are right. I don't think we should do that kind of automatic repetitive historical narrative. I don't think history works that way. Mark Twain's saying that "history doesn't repeat itself but it often rhymes" is very useful. I do think there are several points from the 1920s that are very relevant to our current moment. One is the technological aspect. That was indeed a moment of a new era, especially in terms of electrical technology and mass production. That was the era of Ford.

Essentially, that was the time when Fordism became a global phenomenon and a social model. It was a contract of high wages, high investment, and high consumption, which, at its best, stabilized high levels of consumption and the growth model of the 20th century.

But I think more ominously, I really found Mark Carney's speech yesterday shocking. One thing we tend to forget when we talk about the 1920s is that for most contemporaries, it was the first moment of polarization. It was the moment they believed the forces of liberalism had triumphed. Why? Because the liberal powers won World War I. The 1920s followed this epic revolutionary war, the first total war. And the victorious powers, in a sense, still controlled the situation for a time.

The end of hegemony that Mark Carney talked about yesterday afternoon—whose hegemony was it? In other words, the British Empire, the French Empire, and the United States, two republics, outstanding liberal imperial powers, while Russia, their only ally, succumbed to revolution in 1917 and became a more radical force The foundation of their power is money. It is finance. It is the dollar hegemony of the 1920s, which should have anchored this originally very fragile world. So for me, the lingering... the lingering revelation of the 20s is: this is our first attempt. I mean, collectively, people like us, the first effort to stabilize the world, we failed politically, with the famous Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations. We thought technology and finance would be a good substitute. For a time in the 1920s, this formula seemed to work, as the gold standard system ultimately turned into an increasingly dollar-centric system. Yet arrogance, a failure of imagination, and political failure never provided support for that structure. But I did not anticipate that in my lifetime there would be such a moment, to talk about the 1920s and have Ms. Lagarde appear on stage. The difference between (this) economic power, productive power, and the reliance on money (especially the dollar), and the failure to establish deep political connections in this context, is the true meaning of the 20s for me. That is why it resonates so much with me at this moment, because the key power here is the United States, and the key power of the 20s was also the United States. Those new technologies are American. The important money is American. And it is essentially the United States, for domestic political reasons, that has violated its hegemonic obligations.

Host: Ms. Lagarde, welcome. Thank you for joining us. We are very pleased to have you here. If I may, I would like to ask you a question right away. The reason I am asking you is that you gave a speech in the fall of 2024. You said you believe there is actually some parallel relationship happening between the AI bubble of the 2020s and the 1920s. You said today that, like back then, while we are making great strides in technological advancement, we are also seeing setbacks in global trade integration. We want to try to place this moment in historical context. So I hope you can elaborate and explain what you mean.

Lagarde: I am very happy to. Thank you very much for inviting me. I apologize for being late; it was originally scheduled for 9 o'clock, but I had a commitment at 8:15 that I had to rush over from where I was. I believe Adam has already talked about the political similarities and differences, so I won't delve into that.

What I meant in that speech—going back to 2024. Things have changed since then, and they have not improved. What I want to compare are the technological breakthroughs that occurred in the 1920s. Whether you look at the scale and scope of the electrical grid, the development of the internal combustion engine, or the assembly line that was being developed at that time, those were breakthroughs that happened in that era. At the same time, you also had a very strong stock market. What we observed in the 20s, perhaps Adam you mentioned this, was a significant change in global trade. I wouldn't call it a collapse, but it fell from 21% of GDP to 14% over a few years.

So what we are seeing now is the rapid digitization of our economy, particularly focused on artificial intelligence. We see the stock market performing exceptionally well, not only in developed economies but also in emerging market economies. We have witnessed the fragmentation of geopolitics, and there will be more discussions on this later, accompanied by an increase in tariffs and import-export restrictions across almost all product categories.

This is unprecedented. As long as the WTO is still observing these restrictions, we have not seen trade collapse as I mentioned in the numbers. Not yet. It is still being maintained. It has slightly decreased, but it is still being maintained. The question is whether this can be sustained. But if you give me a little more time, I want to point out a key difference between the 2020s and now, which makes the current situation somewhat more unpredictable and possibly colder. I just came back from the cold outside.

"Cold" is an appropriate word. The difference is that the breakthroughs of the 1920s could spread within national borders—in simple terms. In that era, you didn't necessarily need that scale and network effect.

Now, if you ask the giants in the digitalization field and the big players in artificial intelligence, by the way, developing a cutting-edge model today costs about $1 billion. If you ask them what they need, they will say they need access to as much data as possible. They will say they need scale effects to truly amortize the investment costs of model development. Now, if we face restricted data access due to different privacy laws around the world and more protectionist barriers, that will be severely threatened, hindering the scaling of these investments.

I may have an overly negative and pessimistic view of what we are seeing, but I believe this is a real threat. The development of AI and the productivity gains we hope for are difficult to reconcile with the fragmentation in standards, licensing, and access. I believe this can only be remedied through a certain degree of cooperation. It will depend on whether people are willing to accept and tolerate different paradigms, different cultural preferences, and different worldviews. This is difficult.

Host: Larry, if you can, please talk about this issue because I can see you are thinking about it.

Larry Fink: Well, I have spent a lot of time on this issue. I think what Lagarde mentioned is not only the foundation of significant issues. But I will slightly shift the perspective. I believe that for Western economies, if we do not cooperate, if we do not scale, we will fall behind. I think when people ask me, "Are we in an AI bubble?" this will be one of the overwhelming major issues. I say I think there will be some big failures, but I do not believe we are in a bubble. That said, I would prefer to say we need to spend more money to ensure we remain competitive. So for me, all the issues raised by Lagarde are obvious, and we could have...

The problem we need to solve now is that everyone believes AI will generate a huge J-shaped curve demand for information. The key is to ensure that this demand only arises when the technology spreads to more applications and more uses. If the technology is just the territory of six hyperscale companies, we will fail So for me, and you know, we don't have enough information yet. The key is how fast we can spread it and how quickly it is adapted and adopted; for me, those will be two key characteristics. The parallel point from 1929 evolving into 2029 for me is that the limiting factor will be: can we grow the economy fast enough to overcome our deficits? That could be a big issue, especially considering the rising deficit in the United States. Secondly, do the capital markets have the capacity to continue funding these investments, enabling Western economies to achieve that J-curve of technology adoption? Let me...

Host: I want to ask Ken this question. This actually reflects what Larry has been talking about over the past few years. In fact, Larry, you wrote a letter called "Financial Democratization." That was a phrase used in the 1920s. There was indeed a real effort to democratize finance, raising funds from the public. There was massive debt funding that decade, and I wonder how you view the systemic risks of this moment, the concentration of AI, and the debt funding some of it. I know some mega-corporations are obviously extremely powerful and have extraordinary funding, but there is also a lot of debt flowing behind that.

Ken Griffin: First of all, it's great to be part of this "Gloom and Doom" panel discussion.

Host: Yes, we're not that pessimistic, you know, the 1920s were an extraordinary time. As I said at the beginning, this is not predetermined.

Ken Griffin: The footnote of the 1920s is certainly the Great Depression, Andrew. So let's take a step back and talk about where we are at this moment. The recklessness lies in government spending around the world, with very few exceptions, they are all running deficits. That is the recklessness of this historical moment. In terms of private capital markets, this is not similar to the 1920s. This is a story about government spending recklessly within the private sector.

There is a huge question mark about where AI will take us. I took careful notes listening to what Larry had to say or what Ms. Lagarde had to say because this is one of the big questions of our moment.

Will AI create the kind of productivity acceleration that governments in Washington and around the world sincerely hope for? As a way to overcome the profligate spending we are currently engaged in. It's as if the world needs a savior, and the hope is that AI is the productivity savior we need. And the challenge is that it may be, or it may not be; we just don't know yet.

There is a lot of hype around AI right now. In a sense, large AI companies need to create this hype to raise tens of billions or even hundreds of billions of dollars in investments to enter the field. You can't raise (without the hype)... We will spend hundreds of billions of dollars. Larry might be clearer on this, but capital expenditures for data centers in the U.S. this year are about $600 billion.

Larry Fink: I think there will be more.

Host: But does that mean it has been overhyped? Or is the hype just necessary as a sales mechanism?

Ken Griffin: Right?

Larry Fink: First of all, many of the data centers being built are for cloud services, right?

The big question will be the monetization of the spending. Data centers built for AI require more advanced chips. The question is, what is the lifespan of that chip? If we have a new technological revolution and the lifespan of the chip is only a year, then that spending will really be a bad expenditure. If the lifespan is four or five years as they expect, and then those chips can be used for cloud services, then I think those investments will prove to be good investments. So I think this will be, you know, if the pace of technological change... now all of these investments, they will be, this will be a challenge, but... I agree with Ken's point. I think we don't understand enough, but I am personally very optimistic about how AI will impact the world.

Host: Ms. Lagarde, may I ask you a question related to the amount of debt in today's system that Ken raised? Not talking about corporate debt, but public sovereign debt. The reason I ask is that in the 1920s, at least in the United States, there were budget surpluses. I believe many other countries at that time also had budget surpluses, though not everywhere. But today in the U.S., there is $38 trillion in debt. The script we learned after 1929 is: when a crisis occurs, what do you do to contain it? You throw money at the problem. Ben Bernanke learned this and implemented it in 2008. We did it again during the pandemic. What I've been thinking about is, when the next panic happens—there will certainly be some form of correction—will politicians say, well, we have a script now, we know what to do, we are going to write a $5 trillion check because that’s what we should do? Except for one thing, we’ve been wondering if there is some invisible line in the bond markets around the world? If it accidentally turns into a red line, the investor class will say, “We’re not paying anymore.” And by the way, you would enter a tightening vicious cycle.

Lagarde: Two things. I’m not going to answer your question immediately because I want to go back to a point that both Larry and Ken mentioned. I do not deny that investment in artificial intelligence can be extremely net positive and will bring productivity gains, although the amount is questionable. There is a wide range of opinions on how much benefit it will bring.

But I think going back to my point about “minimum cooperation,” we also have to consider that it is capital-intensive, energy-intensive, and data-intensive. We need to pay attention to these three aspects. In terms of energy intensity, what kind of energy is used to manage data will be important. What the consequences will be for humanity is also very important. So I think while we need this cooperative approach (including dealing with data privacy and preferences in different corners of the world), we also need to pay attention to energy consumption, types of energy, and their impact on the climate Second, we must pay attention to the consequences for humanity, because unless you know, we enter Keynes's dream world where work is a choice—I do not see this in the medium-term vision—we must understand what it means for humanity, unless we want to risk social chaos.

Now, back to your point. Yes, debt has increased significantly, and in some corners more than others. I think the real question is what that financing accumulated by sovereign nations is being used for. Not all debt is the same. Debt invested in necessary productive projects or necessary debt for security purposes will always find someone to fund it. That is my assumption. Debt that is not used for productive purposes and cannot sustain growth on a sustainable basis will be much more difficult. So I won't tell you there is a red line. I also won't tell you that central banks will always be there. But I think the nature of the purpose of debt subscription will be more important than the actual volume.

Host: Talk about what you just said. You just said something very...

Lagarde: Interesting. Talk more about it.

Host: No. About the idea that central banks may not always be there, what do you know about that?

Lagarde: Listen, I have been through many crises, and many of you have too. I remember those days when people mentioned, you know, "the central bank is the only game in town (the only lifeline)." That is not the right way to achieve balance and lasting equilibrium.

Measures must be taken by fiscal authorities, and reforms must be made. The purpose of spending must be carefully considered, and if we want to keep society united, we must consider the consequences for the people.

Ken Griffin: Not just trying to put words in your mouth, but you are basically saying that in our legislative bodies around the world, we have abandoned the responsibility of fiscal prudence and thoughtful use of social resources, becoming overly reliant on central banks to keep the economy on the right track in the face of the shocks from this reckless spending?

Lagarde: I am not suggesting that this is the case now, but it has been observed in the past.

Adam Tooze: I mean, the irony of history is that when people talked about central banks being the "only lifeline" in the 1920s, they were actually urging for more aggressive fiscal policies, right? Because the problem is that we have a low inflation environment and stagnation, including prominent figures from BlackRock advocating for more confident fiscal policies, because there is a profound imbalance between the two levers of macroeconomic policy, which is also a lesson from the 1920s. And now, as Ken suggests, what you advocate, I understand to be a more abstract claim that every government department has a responsibility. Yes, this responsibility involves not only macro totals, as I hear you say, but also specific types of spending. Your distinction between productive and non-productive is not only for economic purposes but also for the key issue of political legitimacy and social cohesion. Because the social contract in Europe and the United States, but in fact in Europe, is under profound pressure from the idea that the modern welfare state is non-productive, and there is a lot of very vicious distributional struggle, which is awakening another ghost of the 1920s, namely the ghost of fascism, right? Some participants are very eager for us to give more platforms to political parties; they are the traditional direct successors. They are now mobilizing in Europe, attacking the legitimacy of public spending, focusing on productive, non-productive, national, international, immigration, racial, and national issues. So this is why this politics is explosive.

Larry Fink: But Adam, in the 2000s, the mantra of "too big to fail" (as Andrew wrote), led to a social perspective of: do not bail out. So there wasn't as much fiscal stimulus as necessary. But I would say the lesson learned from 2020 is that you could argue we used massive fiscal stimulus, perhaps too much, looking back. So I actually believe, you know, we are all evolving, we are deciding which lever to pull. So I think, you know, Europe, especially after 2008 and 09, may not have used enough fiscal tools. But, you know, we see... but in the 2020s, because of COVID, we may have used too much fiscal stimulus. So...

Adam Tooze: It also depends on what kind of structure you have. To emphasize again, because Europeans have jobs, they essentially have short-time work systems to keep people employed. In contrast, in the U.S., the unemployment rate soared in 2020, without a real national unemployment insurance system in operation, having to rely on this "sugar high" of trillion-dollar checks mailed to households to rescue American society. It’s easy to overdo it. Look, in my view, this is one of the great macroeconomic success stories of modern times. It really is, but you are absolutely right, the lesson here, undoubtedly dramatic since the 1920s, is that we did not have another 1929. That is a key point.

Host: I have another question for Ms. Lagarde, actually about the relationship between central bank independence and the political class. I ask this question not just because of this specific moment.

Larry Fink: No. It just happens to be Wednesday.

Lagarde: No, but this... no, but this touches on an interesting parallel. This touches on an interesting parallel. If you look back at what actually happened in the 1920s, especially in 1929. I have read some diaries of members of the Federal Reserve during that period. They were very concerned about the politics at the time. They were very aware of the politics. By the way, it wasn't the president at that time, President Hoover, telling them exactly what to do. Rather, they were worried that the central bank itself would... it was still considered an experiment at that time. It was still new.

Larry Fink: (Would be) dissolved.

Host: You would talk about whether the central bank president would still be here; they were uncertain about what they were doing, uncertain whether they would upset the balance, whether Congress would say, we've had enough of you. So I wonder, during these crises, there are also many times when central bank presidents have to work hand in hand with the Treasury and the president. So we are at this moment. You have recently spoken out publicly You know, a letter was signed regarding what is happening in the United States and our Federal Reserve. What do you think?

Lagarde: First of all, I want to distinguish... hats off to your work because you have really studied in detail how they were thinking during those days and what their fears were. But I would distinguish today’s kind of “cooperation”—which we did to some extent during COVID, let’s face it—from “fiscal dependence.” So, cooperating in exceptional circumstances, even if it is extremely special, I think is completely legitimate. Whether too much was done, I think we should, that’s a good debate.

What form it takes is also an interesting question because between the shock absorbers on this side of the Atlantic and direct fiscal spending to consumers, I think you know there is no conclusion yet about which is more effective. But fiscal dependence is another matter, and I strongly oppose it. You know, for me, the great champion and hero who broke this dependence on central bank governors is Volcker. He took risks.

Huge risks that really affected the economy, jeopardizing the economy, to ensure lasting price stability. I think his position in front of President Nixon at that time, to demonstrate the independence of the central bank to restore price stability, is something we should, you know, keep in mind. I’m not going to comment on what is happening right now, including today, actually. Just to say that I and several other colleagues did take the initiative, in the context of events that happened a week ago, to advocate for the independence of the central bank.

Adam Tooze: One of the truly fascinating things is that the concept of central bank independence itself is a product of the 1920s. It is a product of the 1920s because most central banks, unlike the Federal Reserve, are ancient institutions. Like the Bank of England, the Banque de France. What they had to deal with in the early 20th century was the emergence of modern democracy, namely multi-party systems, populists, social democrats, and right-wingers. It was in this context that the Federal Reserve was born in a sense out of crisis; one of the reasons the U.S. did not establish a central bank earlier was that it was a democratic country, and capitalist democracy is contentious, and money is contentious in capitalist democracy. Central banks are also highly contentious; the U.S. only achieved this when Wilson reached a compromise in 1913. And others, the British, the French, the Germans, of course, had to really figure out what it meant to be a market-oriented, finance-centered bank in a practically active social democratic system. It is from this that the concept has been hostile to populist democracy from the very beginning, and has been so since the 1920s.

That phrase is Montagu Norman's, “knave proof,” right? You want the central bank system to be able to guard against that kind of pressure. There is some resonance in the current moment, right? You need to make the central bank institution able to guard against that kind of political pressure. I think since Volcker, this has been a fruitful place to think about the relationship between expertise, politics, and market pressures. People may have different views on Volcker, but I completely agree with your point that he set the paradigm for modern independent central banks, whether people like this paradigm or not, but it is clearly a defining moment from Carter to Reagan Withstood the pressures during President Reagan's term, etc. But...

Ken Griffin: Just to put things in context. Modern central banks represent the reality that we are not on the gold standard, which was during our time in Vietnam (war)...

Adam Tooze: Fact.

Ken Griffin: Going back 150 years. I'm not advocating that we should implement the gold standard, just that this is a very different world. Then today, and the second significant difference when looking back over 100 years is that debt is everywhere. In a market economy, if you have...

Host: Where there is debt...

Ken Griffin: It's everywhere, deflation.

Adam Tooze: His... is very scary. Well, that's the reality. In the 1920s after World War I, debt was also everywhere. The debt to GDP ratio in post-war Europe was higher than ever before. No one implemented the gold standard after World War I. So in reality, they had to manage democracy, deal with 140%, 150% GDP debt, and figure out how to do central banking. Surprisingly, they chose the gold standard. So at that time, Britain, France, Germany, none of them were on the gold standard. And Italy in 1919, when the 1920s began, they all had to return there by converging with the United States. This became the major conflict between Keynes and Winston Churchill in the 1920s: What price will we pay? This is the Cross of Gold. In the U.S. it was William Jennings Bryan. In Europe in the 1920s. What price will we pay for re-stabilization? This is why it looks and feels like the bad Eurozone of the 1920s.

Lagarde: Right? But there is also a huge difference between then and now.

Adam Tooze: Because those...

Lagarde: The results of monetary policy were completely rigid, while we have more flexibility and more tools to use.

Adam Tooze: Thank God for that.

Ken Griffin: And there are plenty of success stories. I mean, if you look at price stability in Europe, I don't want to jinx it, but it really looks good right now.

Lagarde: Thank you.

Host: Larry. I think you want to take the topic in a different direction.

Larry Fink: Yes, I want to bring it back to today and what we need to pay attention to. I think this is the foundation for thinking about the World Economic Forum and Davos in 2026. That is how technology will reshape many parts of society, whether we get the data right or not. From BlackRock's perspective, we see an increasing number of industries exhibiting a K-shaped economy. Yes, a huge super-winner and many losers. Almost every industry's winners are scale operators who have the opportunity, internal cash flow, and profitability to leverage AI faster. Take Walmart as an example; they have extremely excellent knowledge of inventory control, which almost surpasses any other retailer When consumers buy things, they immediately understand consumer preferences as items are taken off the shelves, allowing them to navigate and compare one store to another. You see this in their performance. You see them performing excellently quarter after quarter over a period of time, achieving higher returns, while many retailers are really struggling at this time. We have bankrupt assets and so on. I see this in every industry. We may see this in every country now, where scale operators are winning, and this has not translated into a broadening of the world economy. In many ways, it may be narrowing. For me, this goes back to what Lagarde talked about; how quickly we can see the adaptation and democratization of AI and technology will be the real key point. Can AI be cheap enough? Can it be widespread enough? So that it can be distributed to small and medium enterprises, allowing them to grow and have the same advantages as scale operators.

But during this time, scale operators are winning. I mean, I see this in the asset management industry, where scale operators have better connections because they leverage more technology. I think this is just in the initial stages, and it will represent some huge social issues.

Host: I can slightly shift the topic and throw out another big question that actually did not happen in the 1920s but technically happened in the 1930s, which I think is very important to everyone. Talking about parallel lines, in 1930, President Hoover, who was very eager to win votes in the 1928 election, promised farmers that he would implement tariffs to gain their votes. The year 1930 arrived. We had already experienced the crash of 1929. Every economist and banker was kneeling in Washington saying, please don’t do this. I beg you, do not implement these tariffs. Of course, because he made this promise to gain those votes, he said he needed to push it forward. Then, of course, a year later, trade fell by 60%.

I’m curious how you think about this issue in the current context. I think the president might even talk about tariffs later today. And it’s not just about what happened when trade fell by 60% at that moment, but also about how long it actually took, for political reasons, to effectively lift those tariffs and bring us into a more globalized order, which may be deconstructed at this particular moment. Who wants to answer this question?

Adam Tooze: I mean, I hear Larry’s suggestion not to talk too much about history anymore. So I want to turn to the present and say the biggest difference is this issue of fiat currency. Because what really led to the collapse of global trade in the early 1930s was the combination of tariffs and monetary chaos, the collapse of the gold standard in 1931, and then the introduction of a large number of quotas. In the current moment, we are a long way from such a world, so while these are bad, it looks more like classic trade war-type tariffs. This is not good, especially considering the volatility of the current tariff regime. That’s what really makes it strange. Historically, we actually don’t know what the tariffs in the U.S. will be next week. But this, I think, is a relative comfort This is a focal point where I don't think there is reason to panic.

Host: But I would ask Ms. Lagarde, do you think these tariffs are a permanent state? If we sit together 20 years from now, will the tariffs we are experiencing today still exist to some extent, as well as the kind of division in our global landscape?

Lagarde: I certainly hope not. But let's see, 20 years from now, you might be here, and I might not be. But, you know, again, I think it's important to delve beneath the surface of those tariffs and see who is bearing the brunt. We might be surprised. You know, I haven't seen a lot of research, but there is certainly a study from the Kiel Institute in Germany that identifies American consumers and American importers as the main bearers of the tariff burden. If I look at U.S.-European relations now, from a 2% tariff, but a year ago, our average tariff in the Eurozone was over 12%. With the looming threat, if targeted, we will average up to 15%. If 96% of that burden is borne by American consumers and American importers, then I don't think that's a good outcome, especially in terms of inflation. So I think we really need to dig into what the consequences are, what the spillover effects are, what the inflation outcomes are as a result, and how growth is affected by this.

Host: Ken, are you calculating this? What do you think?

Ken Griffin: So, you know, obviously, I've spoken on this topic over the past year or so. Unfortunately, I think some of the concerns I've raised have come true. Tariffs are regressive for American consumers, and we see the government removing tariffs on goods that directly affect American consumers, not all goods, but they have removed tariffs on many goods. Second, who pays for the tariffs, right? For any tax, tariffs are a form of tax, and there is always the question of who pays the tax. In this case, it seems that two or three studies have been done showing that the burden of this tax falls on American consumers and American companies, rather than foreign companies. Then, of course, cronyism is the ongoing fear brought by tariffs; you create an environment where the companies closest to Washington are those that are pleasing the powers that be, which puts small businesses at a real disadvantage.

I want to touch on a point here, going back to your comments about the rise of these very large, successful companies. Most of them started as small businesses in our lifetime, right? The person to my right runs the largest asset management company in the world. He founded the largest asset management company in the world and built that business in less than a lifetime. This is a huge success story.

This is the story of American economic vitality, where small businesses can rise to become global leaders in just a few decades. In fact, **if we look at today's AI companies, everyone is talking about Anthropic and OpenAI. Anthropic didn't exist a few years ago. OpenAI didn't exist 15 years ago. NVIDIA is a company that manufactures video game processors The names of the three largest mind shares in the AI field are actually all under about 10 years old. It is precisely this vitality that attracts capital to the United States, truly reflecting the prosperity of the American economy. We need to continue to protect the opportunity set for our small and medium-sized enterprises because you never know which one will become the next BlackRock, the next Anthropic, Apple, and so on.

Host: Larry, I have a technical question for you. One of the reasons we actually had a crisis in 1929 was technology. Do you mean that the New York Stock Exchange couldn't keep up with the trading volume, in fact? I mean, you see those famous black and white photos of thousands of people standing outside the New York Stock Exchange, that was during the crash in October 1929. They were standing there because they were trying to figure out what happened to their money. They didn't know because the processing was too lagged. Today, we can get that information on our phones, accurate to the millisecond, almost perfectly.

However, at the same time, talk about the idea that rumors can spread and propagate very quickly. You know, in the old days, it took a long time for some bad rumors to spread. And by the way, it also took a long time to correct that rumor in terms of efficiency. But today, we saw this with Silicon Valley Bank in the U.S., for example. The moment someone says and publicly states, "I'm going to move my account from this bank," everyone can rush to the exit. Because they can see everything in a completely different way, so while technology is amazing on one hand, I wonder what you think the risks are on the other hand.

Larry Fink: So I would argue that through transparency, the risks are actually smaller. I think Silicon Valley Bank was a poorly regulated bank. I mean, in fact, BlackRock was asked to study their asset and liability portfolio, and we identified it as the most mismatched bank in the U.S. two years before it collapsed. So I think that was a regulatory failure, not a failure of information transmission.

I truly believe that when you talk about other things. I mean, the transmission of information is processed. Yes, we may have quite extreme daily fluctuations at any given time. But we forgot one thing in 2025. If you pick the first day of each quarter, the 10-year Treasury moved 3 basis points. That's all it did, January 1, you know, April 1. Then the 10-year Treasury moved three basis points? Yes. But between those quarters, there were huge fluctuations, you know, and... but that’s the efficiency of the market. That’s the wonderful thing created by Citadel, the rapid movement of funds balances it out, and we determine what fair value is in a very short time. I think that’s the grandeur of capital markets.

Transparency is the engine, I would say. The engine of market movement, Ken should answer this question because he is one of the geniuses in this architecture.

But I would say, back to technology for a second, yes, I think the move towards tokenization and decimalization is necessary. Ironically, we see two emerging countries leading the world in decimalization and the tokenization and digitization of currency, which are Brazil and India I think we need to move very quickly in that direction. We will reduce costs, and we will democratize more by reducing more costs. If all our investments are on a tokenized platform, we can move from tokenized money market funds to stocks and bonds and back again. We have a common blockchain. We will, you know, we can reduce corruption. So I think, yes, we may rely more on a certain blockchain, we can discuss that. That said, these activities may be handled more securely than ever before. We...

Host: We're running out of time. Ken, very quickly. When you think about the technical aspects of this now, I want to know if you think the benefits outweigh the risks for society, but I do want to know if you think the technical aspects represent risks we should be thinking about.

Ken Griffin: The technology of our financial markets is still technology...

Host: Macro-level technology. I mean, I think the financial markets are much safer because of (technology).

Ken Griffin: Look, there's a simple, you know, everyone talks about how difficult this historical moment is. Well, you could live the life you have today, or you could have been born 200 years ago as the King of England. Which life would you prefer?

Adam Tooze: You're somewhere...

Host: Last word. I want to give the last word to Ms. Lagarde. We’re out of time.

Adam Tooze: You are... though.

Host: Okay, historically, what year do you think we are really in? What is the closest analogy?

Lagarde: You know, I think of Hamilton's question to King George, "What comes next?" I think that's what we all want to know, what comes next. But I think we all have a responsibility for what comes next. And my "minimum cooperation" is the plea I want to put on the table right now.

Host: Ms. Lagarde, Adam, Ken, Larry, thank you for your conversation