SemiAnalysis in-depth report: The U.S. power grid can't keep up, AI data centers are racing against time to "build their own power plants"

In the reality where public grid construction takes at least ten years, leading American AI laboratories such as OpenAI, xAI, and Google collectively bypass the grid and build their own gas power plants to get computing power running as quickly as possible. The underlying logic is that when AI enters the stage of ultra-large-scale deployment, the power issue has upgraded from a "cost issue" to the primary constraint determining whether computing power can go live on schedule

In the war of AI, the exponentially growing demand for computing power is crashing into the aging and slow public power grid in the United States. The conclusion is brutal and clear—those who wait for the grid will be eliminated.

To avoid being eliminated by time, an increasing number of AI data centers in the U.S. are doing something that was almost unimaginable in the past: instead of waiting for the grid, they are directly building power plants on-site. Gas turbines, gas engines, and fuel cells are being rapidly deployed next to data centers, all for one goal—to get the power connected as soon as possible and get the computing power running.

On the last day of 2025, the well-known semiconductor and computing power research institution SemiAnalysis released a paid in-depth report over 60 pages long—"How AI Labs Are Solving the Power Crisis: The Onsite Gas Deep Dive." The report systematically outlines the underlying logic of this change: As AI enters a stage of large-scale deployment, the power issue has upgraded from a "cost issue" to the primary constraint determining whether computing power can go live on schedule.

The Essence of the Power Crisis: Not Insufficient, But Too Slow

In traditional understanding, there is no systemic "power shortage" in the U.S. However, SemiAnalysis points out that the real bottleneck faced by AI data centers is not whether power resources exist, but the severe mismatch between the pace of power delivery and the speed of computing power expansion.

The construction cycle for AI data centers has been compressed to 12-24 months; however, the typical cycle for grid expansion, transmission construction, and grid connection approval still takes 3-5 years. When the demand for computing power begins to be released in gigawatts, "waiting for power" itself becomes an unbearable risk.

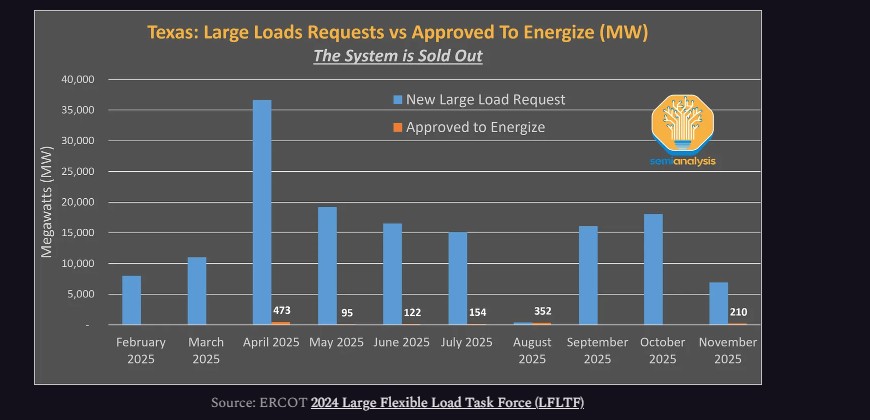

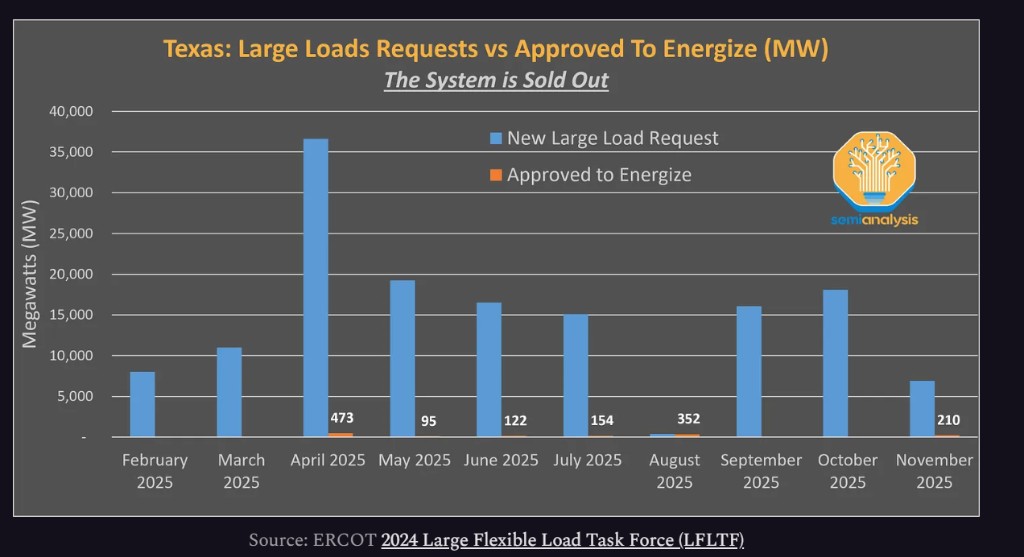

Taking Texas ERCOT as an example, between 2024 and 2025, the scale of new load applications submitted by data centers reached several tens of GW, but during the same period, only about 1 GW of new load was actually approved and successfully connected.

The grid is not out of power, but too slow to match the pace of AI.

When the "Time Value" of Computing Power Outweighs Electricity Prices

Why are AI companies willing to bear higher costs to bypass the public grid?

The answer provided by SemiAnalysis is: the time value of computing power is reshaping all decision-making logic.

According to estimates, a 1 GW scale AI data center can have an annual potential revenue of up to tens of billions of dollars. Even for medium-sized clusters, as long as the launch time is advanced by several months, the resulting commercial value is enough to cover the higher electricity costs.

In this context, electricity is no longer just an operating cost, but a prerequisite for whether AI projects can exist.

"Building Power Plants" Becomes a Real Solution from an Unconventional Choice

Thus, a solution that previously only existed in extreme scenarios has been rapidly brought to the forefront—BYOG (Bring Your Own Generation, self-built power source, on-site power generation) The goal of this model is not to permanently disconnect from the grid, but to "race against time":

- Initially, quickly put into production in an off-grid manner

- Gradually connect to the grid later, with on-site power plants serving as backup and redundancy

In the AI era, going online first is overshadowing the pursuit of optimality.

xAI leads the way, AI giants collectively "self-generate power"

SemiAnalysis focuses on the case of xAI in its report.

In Memphis, xAI built a GPU cluster with a scale of 100,000 cards in less than four months. Rather than a computing miracle, it is more of an extreme operation in power engineering:

- Completely bypassing the public power grid

- Using quickly deployable gas turbines and gas engines

- On-site power generation capacity exceeding 500MW

Even at the equipment level, xAI chose to lease rather than purchase to further compress the construction cycle.

The report shows that by the end of 2025, "self-built power plants" will no longer be an isolated case but will become a systematic trend:

- OpenAI and Oracle are collaborating to build a 2.3GW on-site gas power station in Texas

- Meta, Amazon AWS, and Google are adopting "bridged power" solutions in multiple parks

- Several AI superclusters have been put into operation before completing formal grid connection

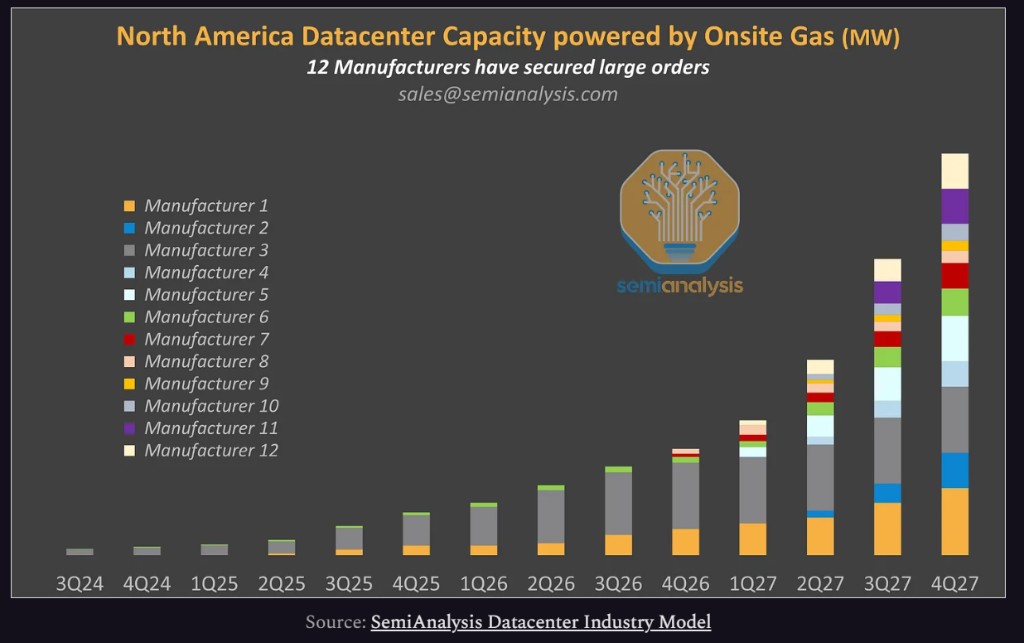

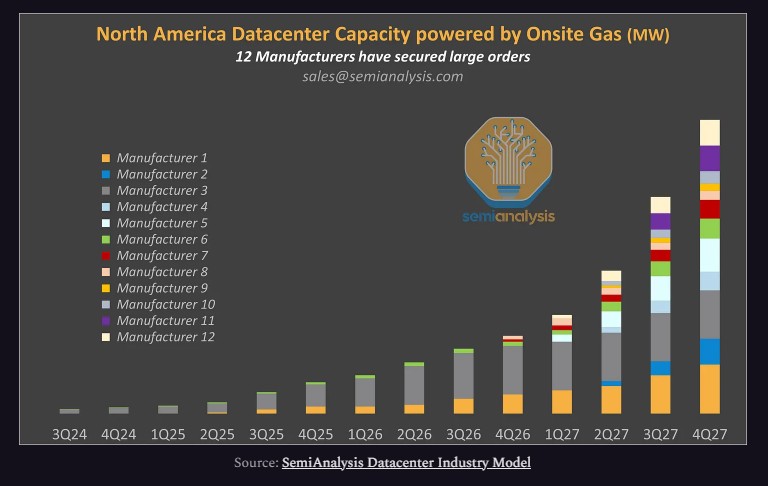

In the United States, more than a dozen power equipment suppliers have secured orders for AI data centers exceeding 400MW in a single transaction. SemiAnalysis believes this marks the first time electricity is viewed as part of AI infrastructure rather than an external condition.

Why natural gas?

Among all on-site power generation solutions, natural gas has become the absolute mainstream.

The reason is not complicated: it is almost the only choice that can simultaneously meet the scale, stability, and deployment speed required by AI.

In contrast, nuclear power has a long construction cycle, wind power and energy storage cannot support high-load operations 24 hours a day, while high-efficiency combined cycle units, although more economical, also fail to meet the "immediate online" time requirement.

In the AI competition, the optimal solution is being replaced by the urgency of time.

Who waits for the grid, who gets eliminated?

SemiAnalysis does not shy away from a reality in its report: the long-term costs of self-built power plants are usually higher than those supplied by the grid. However, in the logic of AI competition, "slow" is more fatal than "expensive."

As computing power becomes the new generation of infrastructure, electricity is transitioning from a public resource to an internal capability that AI companies must master. In this race, what determines victory is not just models, chips, or capital scale, but rather—who can connect power to computing power faster.

The following is the original content of the report, translated with the assistance of AI:

"How AI Labs are Solving the Power Crisis: In-Depth Analysis of On-Site Natural Gas Power Generation"

Aging and Overburdened Power Grid

About two years ago, we first predicted the impending power shortage. In our report "The AI Data Center Energy Dilemma - The Race for AI Data Center Space," we forecasted that AI power demand in the U.S. would grow from approximately 3 gigawatts in 2023 to over 28 gigawatts by 2026—this pressure would overwhelm the U.S. supply chain. Our predictions have proven to be very accurate.

The following chart illustrates the problem: in Texas alone, dozens of gigawatts of data center load requests flood in each month. However, in the past 12 months, only slightly over 1 gigawatt of capacity has been approved. The power grid is sold out.

However, AI infrastructure cannot wait for power grid upgrades that may take years. An AI cloud can generate $10-12 billion in revenue per gigawatt per year. Bringing a 400-megawatt data center online six months early is worth billions of dollars. Economic demand far exceeds issues like grid overload. The industry is already looking for new solutions.

Eighteen months ago, Elon Musk shocked the data center industry by building a cluster with 100,000 GPUs in just four months. Several innovations contributed to this remarkable achievement, but the energy strategy was the most impressive. xAI completely bypassed the grid, using truck-mounted gas turbines and engines to generate power on-site. As shown in the chart below, xAI has deployed over 500 megawatts of turbines near its data centers. In a world where AI labs are racing to be the first to have gigawatt-level data centers, speed is the moat.

One by one, hyperscale companies and AI labs are following suit, temporarily abandoning the grid to build their own on-site power plants. As we discussed a few months ago in "The Data Center Model," in October 2025, OpenAI and Oracle ordered the largest on-site natural gas power plant ever in Texas, with a scale of 2.3 gigawatts. The on-site natural gas power generation market is entering an era of triple-digit annual growth.

The beneficiaries are far beyond the usual suspects. Yes, the stock prices of GE Vernova and Siemens Energy have soared. But we are witnessing an unprecedented wave of new entrants, such as:

South Korean industrial giant Doosan Energy, whose H-class turbines are perfectly timed for market entry. It has secured a 1.9 gigawatt order to serve Elon’s xAI—as we exclusively disclosed to our "Data Center Industry Model" subscribers a few weeks ago Wärtsilä, historically a manufacturer of marine engines, has realized that engines powering cruise ships can also power large AI clusters. It has signed a contract for 800 megawatts with a data center in the United States.

Boom Supersonic—yes, that supersonic jet company—has announced a 1.2 gigawatt turbine contract with Crusoe, viewing profits from data center-generated power as another round of financing for its Mach 2 passenger aircraft.

To understand the growth and market share of suppliers, we have established a site-by-site tracker for deploying on-site natural gas in the "Data Center Model." The results surprised us: currently, there are 12 different suppliers in the United States, each securing over 400 megawatts of on-site natural gas power generation orders for data centers.

However, on-site power generation also brings its own set of challenges. As detailed below, the cost of power generation is often (far) higher than that supplied through the grid. The permitting process can be long and complex. This has led to delays for some data centers—most notably, a gigawatt-scale facility from Oracle/Stargate, which our "Data Center Industry Model" predicted three weeks before the Bloomberg headline by analyzing the entire permitting process.

Once again, smart companies like xAI have found solutions. Elon’s AI lab even pioneered a new site selection process—building at state borders to maximize the chances of obtaining permits early! While Tennessee failed to deliver on time, Mississippi gladly allowed Elon to build a gigawatt-scale power plant.

This report is a deep dive into "self-generated power." We start with why the grid is failing, then provide a technical breakdown of every power generation technology available for data centers—GE Vernova's modified turbines, Siemens' industrial turbines, Jenbacher's high-speed engines, Wärtsilä's medium-speed engines, Bloom Energy's fuel cells, and more.

Next, we examine deployment configurations and operational challenges: fully islanded data centers, gas + battery hybrid systems, energy-as-a-service models, and the economic principles determining which solutions prevail. Behind the paywall, we will share our views on manufacturer positioning and the future of on-site power generation.

Is the grid dead in the AI era?

Before delving into solutions, we need to understand why the grid is failing. Fairly speaking, the U.S. power system has been the primary driver of AI infrastructure to date. Aside from Elon, every major GPU and XPU cluster today runs on grid power. We have reported on many of these in our previous in-depth analysis at SemiAnalysis:

"Microsoft's AI Strategy" showcases the vast grid connection facilities serving OpenAI in Wisconsin, Georgia, and Arizona.

Our "Multi-Data Center Training" report delves into Google's massive grid power clusters in Ohio and Iowa/Nebraska, as well as OpenAI's gigawatt-scale cluster in Abilene, Texas, in collaboration with Oracle, Crusoe, and Lancium.

Our "Meta Superintelligence" article outlines their large AI initiatives, which include some on-site natural gas generation but are primarily powered by AEP systems in Ohio and Entergy in Louisiana.

Our "Amazon's AI Renaissance" paper discusses the large-scale Trainium clusters prepared by AWS for Anthropic, similarly connected to AEP and Entergy's infrastructure.

These insights appeared months or years before the official announcements in our "Data Center Industry Model." Our model tracks dozens of large-scale clusters under construction, scheduled for delivery in 2026 and beyond—including their exact launch dates, total capacity, end users, and energy strategies.

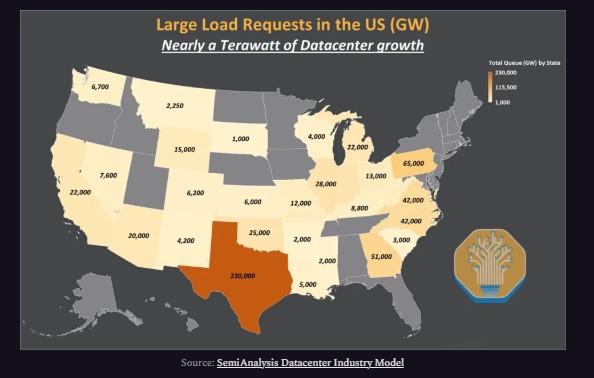

But we have reached a critical point. The large data centers coming online in 2024-25 secured their power supply in 2022-23, before the gold rush. Since then, the competition has become relentless. We estimate that load requests submitted to U.S. utilities and grid operators amount to about 1 terawatt.

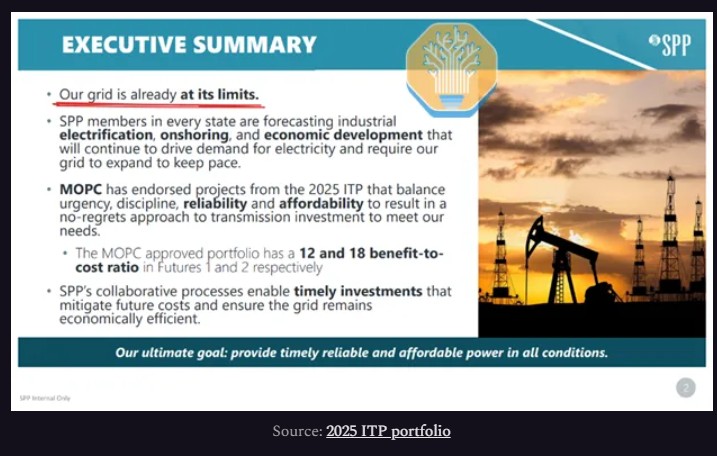

The result is a stalemate—literally. As we explained in "Gigawatt-Scale AI Training Load Fluctuations," the design of the grid makes it slow:

Real-time balancing: The supply and demand for electricity must match almost perfectly, every second. Mismatches can lead to power outages for millions, as seen in the April 2025 Iberian Peninsula blackout incident.

System studies: Every large new load (data center) or supply (power plant) triggers in-depth engineering studies to ensure network stability is not compromised. In some places, the grid topology changes so rapidly that load studies become outdated before they are completed.

When hundreds or thousands of developers submit interconnection requests simultaneously, the system becomes stagnant. This turns into a prisoner's dilemma:

If everyone coordinated, the grid could process more requests faster.

FERC Order No. 2023 has pushed grid operators to adopt cluster studies for this, but these reforms will not solidify until 2025. In reality, the "gold rush" behavior means developers are simultaneously submitting multiple speculative requests to different utilities For example, as of mid-2024, AEP Ohio has 35 gigawatts of load requests—68% of which do not even have land use rights. Speculative requests are clogging the queue for everyone, encouraging more speculative requests elsewhere. This vicious cycle is accelerating.

The supply side is equally constrained. The timeline from interconnection requests to commercial operation has now extended to five years for most types of generation.

AI infrastructure developers cannot wait five years. In many cases, they cannot even wait six months, as waiting six months means losing billions of dollars in opportunity costs.

Introducing BYOG - Bring Your Own Generation

The core value proposition of BYOG is simple: start operations without waiting for the grid. Data centers can rely on local generation indefinitely and then convert these facilities to backup power once grid services are finally in place.

This is exactly the strategy of xAI. They built the "Giant" facility using mobile gas turbines, bringing it online in months rather than years. Now everyone is following this strategy.

Let’s explore how to achieve this.

How to Bring Your Own Generation: Old World vs New World

BYOG involves a complete rethinking of how we build power plants. Traditionally, we deliver electricity through large, centralized gigawatt-scale baseload generators—supplemented by smaller peaking plants to handle load peaks across the grid. Heavy gas turbines in combined cycle mode are the most common modern deployment method. Their unparalleled fuel efficiency (>60%) supports our modern civilization. However, their main issue is deployment speed:

Obtaining large turbines typically requires years of lead time, and current lead times are at historical highs.

Once delivered, the construction and commissioning of large combined cycle power plants take about two years—an eternity in the AI era.

AI data center "bring your own generation" plants are rewriting the rulebook, with xAI leading the way for the industry. To deploy faster, Elon’s AI lab relies on 16-megawatt small modular turbines from SolarTurbines (a subsidiary of CAT). These turbines are small enough to be transported by standard long-haul trucks. They can be deployed in weeks. Elon didn’t even purchase them—he rented them from SolarisEnergyInfrastructure to bypass equipment lead times He also utilized VoltaGrid's mobile truck-mounted gas engine fleet for faster delivery!

Other hyperscale companies quickly followed suit. Meta's deployment in Ohio with Williams is representative — their power plant includes five different types of turbines and engines, clearly following the design pattern of "deploy whatever can be delivered on time!"

Now, let's take a closer look at the different types of equipment available to data center operators.

Overview of Equipment Landscape

The gas generators available to data center developers can be broadly categorized into three types:

Gas turbines - low-temperature, slow ramping industrial gas turbines; high-temperature, fast ramping aeroderivative gas turbines; and very large heavy-duty gas turbines.

Reciprocating internal combustion engines - including smaller 3-7 MW high-speed engines; and larger 10-20 MW medium-speed engines, sometimes referred to as "piston engines."

Solid oxide fuel cells - the main available option currently comes from Bloom Energy.

There are also other on-site power generation options, such as co-locating with existing nuclear power plants, building small modular reactors on-site, geothermal, etc., but these are not discussed in this report. In most cases, these other solutions will not drive net new generation in the next approximately three years.

Understanding which solutions are best suited for certain use cases requires deep core trade-offs. We believe the following points are most relevant:

Cost: Typically listed in $/kW. These cost estimates vary widely and continue to rise across each generator category. Note that maintenance costs are also important: some systems have shorter lifespans, resulting in higher annual maintenance costs.

Delivery time: Typically listed in months or years. As demand grows beyond supply, delivery times are increasing for each generator category.

Note that other factors beyond generator availability can also affect power supply timing. Most notably, even in states like Texas where permits are issued quickly, air permits for on-site generation can take a year or longer.

Additionally, installation times vary significantly between different systems. Some can go from on-site delivery to generation in just a few weeks, such as small truck-mounted turbines or engines, and fuel cells. Large combined cycle gas turbine assembly may take over 24 months.

Redundancy and availability: The expected availability of generators is expressed as a percentage of uptime over a year or "several nines." Over the past decade, the average availability of the U.S. grid has been 99.93% (three nines), with some areas even higher. For on-site power plants, redundancy can be managed by increasing hot standby and cold standby, or by adding backup power sources. The larger a single turbine, the more difficult it becomes to manage standby and backup.

Ramp rate: Measured in minutes from cold start to maximum output. Generators with a ramp rate of less than 10 minutes qualify as reserve generation for the grid or backup power. A slow ramp rate means that the unit primarily focuses on baseload power supply

Land use: measured in megawatts per acre. This is more important in space-constrained areas. Small power generation systems have negligible water usage even when deployed in clusters. However, very large turbines do require a significant amount of cooling water.

Heat rate and fuel efficiency: measured in BTUs of natural gas consumed per kilowatt-hour. A higher heat rate means lower efficiency—more fuel input for the same power output, leaving more waste heat. The nameplate heat rate assumes "peak" operating conditions, typically at maximum output. Efficiency drops significantly below 50% output.

Many of these onsite gas systems can be configured as combined heat and power systems. For data centers, this would involve utilizing the waste heat from gas generators for absorption cooling systems, thereby reducing the electricity consumption for cooling the data center.

In fact, we observe that regardless of other specifications, whoever has open orders and can provide a good schedule tends to win the deal!

That said, let’s dive into the different types of gas power plants.

Aero-derivative turbines and industrial gas turbines—highly attractive for data centers

Gas turbines operate on the Brayton cycle: compressing air, burning fuel within it, and then directing the hot gases to the turbine. The turbines are differentiated by inlet temperature. Lower temperatures correspond to lower installation costs, lower maintenance costs, lower peak efficiency, and slower ramp rates.

Aero-derivative gas turbines are essentially jet engines fixed to the ground. The aero-derivative from GE Vernova is derived from GE's jet engines; Mitsubishi Power's is derived from Pratt & Whitney; Siemens Energy's is derived from Rolls-Royce. Since jet engines are designed to provide immense power in a compact, flight-suitable package, they are relatively easy to retrofit for stationary power generation. Extend the turbine shaft, bolt on generator coils at the end, add intake and exhaust silencers, and deliver fuel from a tank or pipeline. This partly explains why Boom Supersonic can pivot to aero-derivative gas turbines so quickly: most of their engineering and manufacturing is off-the-shelf.

Below, we show a view of the Martin Drake power plant, equipped with six GE Vernova LM2500XPRESS units. This is how utilities deploy aero-derivative turbines as "peaking plants" to address sudden supply shortages in the grid.

The core manufacturers of aero-derivative gas turbines are similar to those of heavy-duty gas turbines: GE Vernova, Mitsubishi Power, and Siemens Energy dominate the market, selling aero-derivative and low-temperature industrial gas turbines. Additionally, Caterpillar also produces industrial gas turbines under the Solar brand, and Everllence also manufactures them.

Two GE Vernova designs dominate the aero-derivative market:

LM2500 – approximately 34 megawatts, optimized for rapid deployment, especially the LM2500XPRESS.

LM6000 – approximately 57 megawatts, now available in a rapid deployment LM6000 VELOX configuration

The aeroderivative gas turbines have acceptable fuel efficiency but are extremely efficient in terms of space and weight. They can be installed in compact footprints and can be transported by a pair of trailers in certain configurations. Simple cycle aeroderivative models typically provide power packages of 30-60 megawatts, capable of ramping up from cold to full load output in 5-10 minutes. However, efficiency is affected if operating below full load stability. Aeroderivative models can also be configured as small combined cycle power plants:

1x1 (one gas turbine driving one steam turbine) or 2x1 (two gas turbines driving one steam turbine). These combined cycle setups offer higher efficiency and more output at the expense of ramp-up speed. Startup time extends to 30-60 minutes.

At current prices, the total capital expenditure for aeroderivative turbines ranges from $1,700-2,000/kW, with delivery times for recent orders extending to 18-36 months. Smaller turbines can have delivery times as short as 12 months, while larger aeroderivative turbines (around 50 megawatts) may take up to 36 months. These systems install quickly (typically 2-4 weeks), but there is a huge backlog of orders. One workaround is to use truck-mounted turbines, which can be quickly rented and deployed if available. xAI has adopted this strategy in collaboration with SolarisEnergyInfrastructure to shorten the power delivery time for its Colossus1 and 2 projects.

Industrial Gas Turbines

Industrial gas turbines operate on the same principles as aeroderivative turbines and share advantages such as compact footprint, modularity, and relatively short delivery times. However, they are designed from the ground up for fixed use rather than being adapted from aviation. They typically operate at lower inlet temperatures and use simpler designs, which reduce service costs at the expense of efficiency and ramp-up speed.

Simple cycle industrial gas turbines have a power range of approximately 5-50 megawatts, taking about 20 minutes to ramp up from cold to full load output. This makes them too slow to serve as peaking plants or emergency backup power without the assistance of batteries or diesel generators. Similar to aeroderivatives, industrial gas turbines can be upgraded to combined cycle configurations to improve efficiency while further slowing ramp-up rates.

The most common dedicated industrial gas turbines are Siemens Energy SGT-800 and SolarTitan series. However, smaller heavy-duty gas turbines like GE Vernova 6B sometimes also take on similar use cases.

At current prices, the total capital expenditure for industrial gas turbines ranges from $1,500-1,800/kW, with delivery times of about 12-36 months, similar to aeroderivatives. However, procuring used or refurbished industrial gas turbines can shorten delivery times to under 12 months, which is how FermiAmerica acquires power.

Overall, we believe that aeroderivative turbines and industrial gas turbines are very attractive solutions for on-site power generation because:

"Right size": Small enough for redundancy, large enough to avoid excessive on-site units that complicate maintenance

Fast ramp-up speed: Although their efficiency is not as good as other solutions, they are easier to be repurposed as backup power sources.

Quick deployment: They can be transported and installed by regular trucks and construction teams, rather than the heavy lifting infrastructure required for heavy gas turbines.

We will explore these concepts when discussing deployment considerations later in the report. The main issue with aeroderivative and industrial gas turbines is the increasingly long delivery times.

The most tightly supplied components in gas turbines are the turbine blades and core machines, which must withstand high temperatures and high speeds. These blades use exotic single-crystal nickel-based alloys containing rare metals such as rhenium, cobalt, tantalum, tungsten, and yttrium.

Reciprocating Engines

Reciprocating engines operate similarly to automotive engines but are much larger, with an 11-megawatt engine potentially exceeding 45 feet (14 meters) in length. They use a four-stroke combustion cycle and are categorized by speed:

High-speed engines – approximately 1,500 RPM; smaller footprint and output.

Medium-speed engines – approximately 750 RPM; typically lower maintenance costs due to reduced mechanical stress.

Reciprocating engines can ramp up from cold to full load output in 10 minutes, which is actually similar to aeroderivatives. This allows reciprocating engines to serve as peaking power plants or backup generators without the need for diesel backup power. Theoretically, the operational and maintenance costs of reciprocating engines appear higher than those of turbines due to more moving parts. However, in practice, they handle fuel impurities, dust, and high ambient temperatures better than many turbines and experience less performance degradation in hot climates.

The medium-speed engine manufacturing industry is quite concentrated, with major manufacturers including Wärtsilä, Bergen Engines, and Everllence.

The high-speed engine manufacturing industry is less concentrated than that of turbines. In addition to major players like Jenbacher, Caterpillar, Cummins, and Rolls-Royce subsidiary MTU, there are numerous manufacturers, as high-speed gas engines are functionally equivalent to the diesel engine designs currently used for backup power in many data centers. The most influential reciprocating engine is the Jenbacher J624, a 4.5-megawatt turbocharged gas engine that can be containerized for logistics. This system is the preferred generator for VoltaGrid's energy integration services.

Reciprocating engine systems typically have lower unit power than equivalent turbines. Medium-speed engines range from 7 megawatts to 20 megawatts, with higher power outputs achieved through turbocharging. High-speed engines are smaller, with unit output power ranging from 3 megawatts to 5 megawatts. However, when operating at 50% to 80% partial load, reciprocating generators are more efficient than turbines.

The operating temperature of reciprocating engines is much lower than that of gas turbines, close to 600°-700°C. This greatly reduces the demand for high-performance alloys. Only the high-temperature components in the pistons, combustion chambers, and turbochargers still require rare nickel and cobalt alloys, while the rest can be made from simple cast iron, steel, and aluminum. However, overall, reciprocating engines have a lower dependency on critical minerals, especially in times of tight material supply when emissions controls are relaxed According to current prices, the total investment cost for reciprocating engines is between $1,700-2,000/kW, with a delivery period of 15-24 months. Compared to gas turbines, these systems have less manufacturing delay; the manufacturing timeline is closer to 12-18 months. However, medium-speed piston engines are significantly heavier than gas turbines, and installation and commissioning can take up to about 10 months.

The deployment of high-speed engines can be much faster. For example, in the initial Colossus1 deployment, xAI utilized 34 VoltaGrid truck-mounted systems, integrating Yanmar's high-speed engines. High-speed engines are particularly favored by energy procurement suppliers. Their widespread availability and small unit size provide faster power delivery times. Below, we showcase the 50 MW deployment of VoltaGrid in San Antonio, equipped with twenty Yanmar J620 engines.

The trade-off lies in scale: to build a 2 GW site gas system with 5 MW engines, you need 500 units! This brings significant operational consequences. If each engine requires minor maintenance every 2,000 hours, maintenance personnel will perform over 2,000 services annually, nearly 40 times a week. These costs are more predictable than gas turbine overhauls (which may involve replacing the entire core engine), but they accumulate, especially for clusters with many small units. Space and spare parts inventory will similarly increase, although the vertical stacking of small generators can alleviate land use issues, which is not possible for medium-speed engines.

Fuel Cells and the Rise of Bloom Energy

A relatively niche solution is capturing an increasing market share: fuel cells. Typically associated with hydrogen energy, Bloom Energy's SOFC (Solid Oxide Fuel Cell) can also operate on natural gas and is positioned for baseload power generation. We identified Bloom Energy as a winner in data center models as early as 2024. Since then, orders have surged.

Bloom's "Energy Server" consists of multiple stacks of about 1 kW, assembled into modules of approximately 65 kW, and packaged into 325 kW generator sets. So far, the largest operational SOFC power plants are in the tens of megawatts, primarily in the United States and South Korea.

They generate energy in a way that is very different from traditional generators. There is no combustion process. Instead, oxygen is electrochemically reduced to oxygen ions, which flow through a ceramic electrolyte. On the other end of the fuel cell, these ions combine with hydrogen atoms stripped from methane natural gas. This combination releases water, carbon dioxide, and electrical energy.

This fundamental difference provides Bloom's fuel cells with a key advantage: they do not produce significant air pollution (aside from CO₂). Permitting at the EPA level is much smoother and easier than for combustion generators. This is why we often see them near population centers, such as near offices.

Bloom's trump card is deployment speed. It requires almost only a prefabricated base and simple module installation. Once electrical engineering, installation, and commissioning are considered, it can be completed within weeks, comparable to the speed of modified gas turbines and high-speed piston engines

In the AI era, speed is the moat, and this advantage alone is enough for Bloom to secure a place.

Bloom's main challenge is cost. The fuel cell efficiency is quite good, with an equivalent thermal consumption rate of 6,000-7,000 BTU/kWh, which is comparable to combined cycle gas turbines. However, the cost of fuel cell systems is significantly higher than that of turbine or piston systems, with capital expenditure costs ranging from $3,000 to $4,000 per kW. Bloom has not advertised the ramp rate, indicating that these units are too slow to serve as peaking or emergency backup.

Historically, maintenance costs have also been significantly higher than other solutions. The lifespan of a single fuel cell stack is about 5-6 years, after which it must be replaced and refurbished. This stack-by-stack replacement accounts for about 65% of service costs, although specific figures are strictly confidential.

We will share the total cost of ownership estimates for Bloom fuel cells after the paywall.

Heavy Gas Turbines: The Future of BYOG?

Before the emergence of ChatGPT, only utility companies and independent power producers had reasons to purchase gas turbines larger than 250 megawatts, as turbines exceeding this threshold were too large for most industrial applications. As mentioned, deployment speed is an issue; however, we are increasingly seeing developers provide "transitional power" through smaller aeroderivative turbines/piston engines, which are then converted to backup/redundancy once large combined cycle gas turbines are operational.

Large turbines are categorized based on combustion temperature and technology stack:

E-class and F-class – older designs with lower temperatures and efficiencies. Some F-class units are still being sold, typically entering emerging markets, as they offer decent efficiency with lower capital expenditures. The boundary between industrial turbines and small E/F-class turbines is blurred, with the following well-known models crossing this boundary:

GEVernova6B

GEVernova7E

Siemens Energy SGT6-2000E

H-class and equivalent products – modern, high-temperature designs. The combustion temperatures of these units are comparable to modern aeroderivative and jet engines, but the unit power is about ten times that. The most prominent examples are:

GEVernovaHA series

Siemens Energy H/HL

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries J series

Recently, the South Korean company Doosan Energy has begun producing a new H-class turbine, the DGT6. It is rare to see new entrants in a market with a ten-year history, but Doosan has extensive experience in steam turbine manufacturing and a track record of building F-class turbines based on Mitsubishi designs

These systems are both large and heavy. The installation and commissioning process may take some time.

Combined Cycle Gas Turbine

The combined cycle gas turbine takes advantage of the fact that the exhaust from a simple cycle is still hot enough to boil water into steam. The exhaust is passed through a heat recovery steam generator to produce steam, which drives a separate steam turbine and generator. The result is that the same fuel generates a second round of electricity. By turning the waste heat from one turbine into wealth for another turbine, combined cycle gas turbines can achieve efficiency improvements of 50-80% compared to simple cycle turbines.

The most respected combined cycle gas turbines for large loads are heavy-duty combined cycle gas turbines, which can achieve gigawatt-level output. However, even small aeroderivative or industrial gas turbines can be sold with integrated steam turbines, which can significantly increase power output with nearly the same fuel input. Common configurations include:

1x1 – one gas turbine drives one steam turbine

2x1 – two gas turbines drive one steam turbine

Theoretically, more gas turbines can drive one steam turbine, but with diminishing returns. The main drawback of combined cycle systems is the ramp rate: adding a steam turbine slows the time for a cold start to full load output to 30 minutes or longer.

Another major drawback is the delivery time. The installation and commissioning time is even longer than that of simple cycle deployments.

From Equipment to Execution: Deployment, Challenges, Economics

Understanding the equipment landscape is necessary, but not sufficient. The real complexity of on-site gas lies not in choosing between the LM2500 or the Jenbacher J624—but in how to configure, deploy, and operate these systems to meet the uptime requirements of data centers.

The grid is a marvel of systems engineering: thousands of generators, hundreds of transmission lines, and complex market mechanisms work together to provide an average uptime of 99.93%. When you go off the grid, you take on that complexity yourself—matching grid-level reliability with a single power plant. Redundancy and uptime are key reasons why the cost of on-site gas generation is structurally much higher than grid-supplied power in most cases.

The next section will examine how leading deployments are addressing this challenge and what it means for equipment selection.

Crusoe and xAI: Transitional Power Deployment

One of the most popular on-site gas strategies to date is "transitional power." Data center campuses actively communicate with the grid for power services but begin operations early with on-site generation.

Transitional power removes electricity as an operational bottleneck, allowing data centers to start training models or generating revenue months in advance. This acceleration is significant! AI cloud revenue can reach $10-12 million per megawatt annually, meaning that powering and bringing online a 200-megawatt data center six months early can generate $1-1.2 billion in revenue.

Transitional power brings two advantages:

Uptime requirements can be matched with workloads. For example, in Abilene, Texas, and Memphis, Tennessee, xAI and Crusoe/OpenAI are deploying large training clusters Considering the inherent unreliability of large GPU clusters, training jobs do not require particularly high uptime. Therefore, it is possible to avoid "overbuilding" power plants for redundancy. Once grid connection is secured, the park can be used more flexibly for inference.

Favorable economics are achieved by eliminating diesel generator backups. In Memphis and Abilene, the absence of backup power reduces capital expenditures per megawatt for data centers. Once grid connection is obtained, turbines can serve as backup power—thus, prioritizing fast ramping systems, such as aeroderivative turbines.

To ensure reasonable uptime, xAI pairs turbines with Megapacks. This also enables smoothing of load fluctuations—we will discuss this issue below.

Always Off-Grid: Redundancy Challenges, Energy as a Service

Many generator suppliers advise data center owners never to bother with interconnection to the wider grid; instead, they believe their data center clients should remain off-grid at all times. Companies like VoltaGrid offer complete "Energy as a Service" packages, managing all aspects of power services:

Power – capacity in megawatts and energy in megawatt-hours

Power quality – voltage and frequency tolerances

Reliability – target "several nines" uptime

Supply time – months from contract to operation

They typically sign long-term power purchase agreements with clients, who pay for power service fees—the energy as a service provider essentially acts as a utility company. They procure equipment, design deployments, sometimes assemble material lists, and maintain and operate power plants.

A key challenge in deploying off-grid power is managing redundancy. For example, the 1.4 GW VantageDC park located in Shackelford County, Texas, will deploy a 2.3 GW VoltaGrid system. These systems are smaller and easier to manage for redundancy—but if you are deploying on-site power with large heavy-duty turbines, the redundancy scheme may simply involve having two power plants, or even more.

Generator manufacturers typically recommend at least an N+1 configuration, or even an N+1+1 configuration. An N+1 configuration maintains full generating capacity even when one generator unexpectedly goes offline, while an N+1+1 configuration has an additional generator on standby for maintenance cycles while maintaining this flexibility. This is akin to driving a car with a spare tire and a tire repair kit. Note that N+1 or N+1+1 does not necessarily refer to the literal number of generators, as data center loads are often much greater than a single on-site gas generator. For example, consider a data center with a total power consumption (IT + non-IT) of 200 megawatts:

Example 1: 11 megawatt piston engines

Generator cluster: 26 × 11 megawatt piston units

Total capacity: 286 megawatts

Uptime:

23 engines operate at approximately 80% load, generating over 200 megawatts.

One generator failure: 22 engines moderately increase to approximately 82% load 3 spare engines are used for maintenance or as cold spares.

Operating the engines below full load reduces operational and maintenance costs, and the additional units provide a buffer for maintenance scheduling.

NexusDatacenter has adopted a similar approach: they recently applied for an air permit to deploy thirty Everllence 18V51/60G gas engines, each with a power output of 20.4 megawatts, totaling 613 megawatts of generating capacity. The site will also include 152 megawatts of diesel backup generation, which may meet the N+1 redundancy requirements for the entire site.

Example 2: 30 megawatt aeroderivative gas turbines

Generation cluster: 9×30 megawatt aeroderivative units

Total capacity: 270 megawatts

Under normal operation:

7 turbines operate at approximately 95% load for optimal efficiency.

In the event of a turbine failure: the 8th turbine starts to maintain output.

The 9th turbine is kept as a maintenance spare.

Since turbine overhauls are more disruptive than engine maintenance, some suppliers offer hot-swappable plans: replacing a turbine that requires an overhaul with a replacement core.

In hot climates, such as the southwestern United States, derating may require 10-11 aeroderivative turbines to maintain N+1+1 redundancy.

Crusoe has adopted a variant of this setup for Oracle and OpenAI at their site in Abilene, deploying ten turbines, including five GE Vernova LM2500 XPRESS aeroderivative gas turbines and five Titan 350, with a nameplate generating capacity of 360 megawatts.

Example 3: Meta + Williams Socrates South

Meta and Williams are constructing two dedicated gas power plants of 200 megawatts each to power Meta's new Albany center, which we have reported on in this article: Meta's new ultra-fast "tent" data center in Ohio.

The Socrates South project is a mixed cluster:

3× Solar Titan 250 industrial gas turbines

9× Solar Titan 130 industrial gas turbines

3× Siemens SGT-400 industrial gas turbines

15× Caterpillar 3520 fast-start engines

The nameplate capacity within the enclosure is 306 megawatts: approximately 260 megawatts from turbines and 46 megawatts from engines. Normally, a portion of the industrial gas turbines operates steadily to provide 200 megawatts of power. If one or two industrial gas turbines trip, the piston engine cluster can quickly ramp up to fill the gap. Additional industrial gas turbines can be used for maintenance switching. This supports the dedicated N+1+1 design.

However, compared to the first two examples, this is a patchwork implementation. The turbine models do not match, and the engines used are smaller 1800 RPM high-speed gas engines. This indicates that Williams prioritized uptime over a standardized maintenance plan

Matching Normal Operating Time of the Power Grid: Overbuilding, Backup Power Grid, Batteries

To match the "three nines" of normal operating time provided by the power grid, on-site power plants must be "overbuilt" for redundancy. This is often a key reason why on-site generation costs are relatively high compared to the grid.

Redundancy presents new challenges for operators: there is a trade-off between system scale and the ratio of "overbuilding." While H-class and F-class turbines are more energy-efficient than aeroderivative turbines, the higher redundancy requirements mean that, if not designed properly, island systems based on heavy-duty turbines may incur higher electricity costs than aeroderivative turbines. Other solutions must be considered instead of simply "overbuilding," such as using smaller turbines as "backup," batteries, or even grid connections.

To understand the overbuilding ratio, we can use a practical example. In Shackelford County, Texas, VoltaGrid powers a 1.4 GW data center with a 2.3 GW Yanbahe system, resulting in an overbuilding rate of 64%. We can break it down as follows:

Peak PUE overbuilding: Similar to typical grid-connected sites in Texas, there is a 1.4x-1.5x overprovisioning, mainly related to cooling.

There is also an additional 10-17% overbuilding related to redundancy.

For H/F-class systems, simple overbuilding is often not the most economical path. Some operators consider connecting to the grid solely for backup purposes—but this introduces challenges with interconnection timelines and complicates the site selection process. A massive battery plant could also be built—as shown in xAI's Colossus2 deployment below—but this is both expensive and impractical, as typical storage durations are only 2-4 hours. Finally, different combinations of turbine and engine sizes can be used, with H-class combined cycles running as baseload, and industrial gas turbines/aeroderivative turbines/piston engines as backup—but this is usually more expensive than grid connection or a 2-4 hour battery storage system.

Managing Load Fluctuations

AI computing loads, especially training loads, are highly variable, including sub-second megawatt power spikes and drops. The greater the inertia of the power system, the better it can manage short-term power fluctuations while maintaining power frequency. If the frequency deviates too far from the baseline of 50 Hz or 60 Hz, power fluctuations can cause circuit breakers to trip or equipment failures. All thermal generators have some inertia because they generate power through rotating masses. However, developers can increase inertia through auxiliary systems:

Synchronous condensers—these essentially act as generators that rotate as motors without mechanical loads. Once synchronized with the grid, they consume only a small amount of losses. During sudden load changes, they absorb or supply reactive power, stabilizing voltage and increasing short-term inertia. Their energy capacity is small, so they can only assist for a few seconds, not minutes.

Flywheels—these add a true rotational energy buffer. An electric-generator unit is coupled to a large flywheel and connected between generation and load. Flywheels can inject or absorb active power (not just reactive power) for 5-30 seconds, smoothing transients, generator trips, and voltage sags For example, Bergen provides flywheels bundled with its engines through an affiliated supplier.

Battery energy storage systems – batteries can ramp up as quickly as load changes, providing "synthetic inertia" through high-speed control, as mentioned in the previous article. They excel in frequency regulation, but due to inverter current limitations, their contribution to reactive power and fault current is not as strong as that of synchronous machines.

VoltaGrid combines piston engine clusters with synchronous compensators. Bergen Engines has already sold engines with flywheels through suppliers under the same parent company. The engine manufacturer Wärtsilä has a battery storage division that may bundle it with data center projects. Bloom claims its fuel cell systems do not require any equipment to manage load fluctuations. The specific systems used depend on local constraints but mainly rely on vendor preferences. xAI prefers to use Tesla's Megapack for backup and handling load fluctuations.

Megapacks + MACROHARD

Are we able to build enough gas power plants to power AI?

Currently, the delivery times for gas power systems are unprecedented. Historically, gas turbine manufacturers averaged only accepting orders 20 months before factory shipment, but now the three major manufacturers GEVernova, Siemens Energy, and Mitsubishi Power are accepting orders for 2028 and 2029, with even non-refundable reservations for later dates. Every publicly listed gas system manufacturer has reported an increase in data center demand, but most are responding cautiously rather than with full-scale expansion.

GEVernova has committed to increasing production to 24 GW/year, but this only returns to its levels from 2007-2016. They are investing in new staff and machinery but do not plan to increase factory footprint.

Siemens Energy also plans to invest in production without increasing factory footprint. Instead, they prioritize price increases, rely on service revenue, and focus on investments with short payback periods. They plan to expand annual capacity from about 20 GW to over 30 GW by 2028-2030.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries stated in a recent earnings call that it plans to increase gas turbine and combined cycle output by 30%, which contradicts Bloomberg's report about plans to double capacity by 2027.

Caterpillar plans to double engine production and increase turbine output by 2.5 times between 2024 and 2030, but its Solar brand turbines have an average annual output of about 600 MW from 2020 to 2024, peaking at 1.2 GW in 2022.

Wärtsilä has only committed to gradual expansion, preferring to "wait and see" on data center demand and maintain relationships with maritime customers.

Among the major gas generator manufacturers, only Bloom Energy, Caterpillar, and new entrant Boom Supersonic have announced ambitious expansion plans. Bloom Energy claims it can reach a production capacity of 2 GW/year by the end of 2026, while Boom Supersonic plans to reach 2 GW/year by the end of 2028 At first glance, despite the surge in demand, it seems that very few manufacturers have fully embraced the "general artificial intelligence belief." This hesitation partly reflects real manufacturing constraints; mostly, it reflects the post-traumatic stress disorder from the 30-year boom-bust cycle in the gas power industry. Notably, the most severe bottlenecks are in heavy-duty gas turbines. The limitations of aeroderivative turbines, industrial gas turbines, and piston engine systems are less pronounced.

Two Boom-Bust Cycles of Gas Turbines

Since the mid-1990s, the gas turbine industry has experienced two boom-bust cycles. The first boom, from 1997 to 2002, was driven by deregulation of electricity in parts of the United States, attracting new companies to become independent power producers, and (ironically) the high expectations for electricity demand growth stemming from the internet bubble popularized by Huber and Mills' paper "The Internet Begins with Coal."

Large companies like Calpine, Duke, Williams, and NRG placed massive orders for turbines, pushing the order volumes of GE Vernova and Siemens Energy to their peaks. GE shipped over 60 gigawatts of gas turbines in 2001; Siemens reached a peak of over 20 gigawatts in 2002.

The crash came swiftly. The internet bubble burst, the Enron scandal shook the electricity trading business, and orders dried up, plunging GE and Siemens into a manufacturing winter that lasted for years. The second "boom" in the gas turbine industry resembled more of a stable order state rather than a true boom. Between 2006 and 2016, GE averaged about 20 gigawatts of turbine shipments per year, while Siemens averaged about 15 gigawatts per year. Then, from 2017 to 2022, the market completely collapsed, with the annual output of both GE and Siemens dropping to historical lows below 10 gigawatts.

Both companies have institutional memories of the Y2K gas turbine boom period, as well as recent memories of sales being at historical lows. Notably, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries largely avoided these boom-bust cycles. Until recently, the hardware sold by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries accounted for only a small portion of GE Vernova and Siemens Energy's sales. It became one of the "big three" simply because larger companies had scaled down to its sales level, while other players like Alstom Energy and Westinghouse had either shut down or been acquired. This may partly explain MHI's interest in expansion, although its so-called doubling plan was not confirmed during the earnings call.

Supply Chain Bottlenecks

However, within gas turbines, even with guaranteed future demand surging, it may not drive an increase in output due to internal bottlenecks in the production and logistics of the core gas turbine components.

Gas turbine blades and vanes are among the pinnacles of modern industrial technological capability, requiring extremely high-quality metallurgy and machining techniques to manufacture correctly.

Turbine blades and vanes are some of the most demanding components in modern industrial manufacturing. Their production requires extraordinary metallurgy and machining precision. As a result, Western production is concentrated in four companies: Precision Castparts Corporation, Howmet Aerospace, Consolidated Precision Products, and Doncasters

These companies not only supply industrial and power gas turbines but also civil and military jet engines. Except for CPP, other companies have vertically integrated metal supplies, but their scale is only a small part of their customers, making them more susceptible to market shocks. The second gas turbine downturn coincided with a decline in aerospace orders due to COVID, which means these companies have recently faced considerable setbacks. Increased demand not only requires these companies to hire more specialized employees but also to consider the supply chains for materials such as yttrium, rhenium, single crystal nickel, and cobalt. More importantly, they may be reluctant to make these investments because if they follow the AI bubble off a cliff, they will incur the greatest losses.

Additionally, the production of heavy gas turbines is constrained by logistics. The core of the turbine alone is a 300-500 ton system that requires specialized barges, rail cars, and truck trailers for transport. Even after obtaining permits, heavy gas turbines require 24-30 months to build, install, and test before they can operate. The aftermarket OEM can build new power plants around refurbished cores, but moving and integrating these cores remains a significant challenge. These constraints are less severe for aircraft-modified turbines and industrial gas turbines, which are small enough to be transported using standard containers or conventional trailers.

New entrants to the rescue: From aircraft to ships?

Typically, during constrained periods, many clever companies are exploring solutions. ProEnergy is one of the earliest companies to bring innovation. Its PE6000 project retrofits the CF6-80C2 engine core from the Boeing 747 and provides an operational aircraft-modified gas turbine that is nearly identical in specifications and packaging to the GE Vernova LM6000.

Recently, Boom Supersonic announced the development of the Superpower aircraft-modified gas turbine based on its supersonic jet engine design. Its proposed profile is very similar to the GE Vernova LM2500 and operates on the same principle: a small jet engine that can fit into a container (with auxiliary air intake, control, and exhaust equipment fitting into an additional 1-2 containers). Testing of the engine is still ongoing, but preliminary promotional specifications indicate that even in high-temperature ambient air, Superpower can generate 42 megawatts of power per unit.

The first batch of 1.2 gigawatts has been reserved by Crusoe, with a target of reaching 200 megawatts by 2027, 1 gigawatt by 2028, and 2 gigawatts by 2029. The initial order pricing suggests a hardware cost of $1,000/kW, but this figure does not include balance of system, transportation, or commissioning costs and should not be directly compared to all-inclusive cost data. Boom Supersonic has vertical integration capabilities for blade and stator production but relies on external suppliers for metallurgy, which may still pose a supply chain bottleneck.

We have not yet seen other companies join the ranks of retrofitting. However, medium-speed engines are primarily manufactured by companies with long-standing experience in ship engine manufacturing—such as Wärtsilä. In fact, they are essentially the same engines that can be manufactured in the same facilities. When will we see old marine engines retrofitted to power data centers?

Now let's turn our attention to comparing different solutions and manufacturers. We will also analyze the economics of on-site power generation and total ownership costs, comparing them with the U.S. grid.

New Entrants to the Rescue: From Aircraft to Ships?

Typically, during periods of supply constraints, many clever companies explore solutions. ProEnergy was one of the first companies to bring innovation. Its PE6000 project improved the core of the CF6-80C2 engine from the Boeing 747, producing a modified gas turbine with operating characteristics nearly identical to the GE Vernova LM6000.

Recently, Boom Supersonic announced the development of the Superpower modified gas turbine based on its supersonic jet engine design. Its proposed shape is very similar to the GE Vernova LM2500 and follows the same principle: a small jet engine that can fit into a single container (with auxiliary air intake, control, and exhaust equipment housed in an additional 1-2 containers). Testing of the engine is still ongoing, but preliminary promotional specifications indicate that Superpower can generate 42 megawatts of power per unit, even at higher ambient air temperatures.

The first batch of 1.2 gigawatts has been reserved by Crusoe, aiming for 200 megawatts in 2027, 1 gigawatt in 2028, and 2 gigawatts in 2029. The initial order price suggests a hardware cost of about $1,000 per kilowatt, but this figure does not include balance of system equipment, transportation, or commissioning costs and should not be directly compared to all-in cost data. Boom Supersonic has vertically integrated the production of blades and stators but relies on external suppliers for metallurgical materials, which may still pose a supply chain bottleneck.

We have yet to see other companies join the ranks of modifications. However, medium-speed engines are primarily manufactured by companies with long-standing experience in ship engine manufacturing—such as Wärtsilä. In fact, they are essentially the same engines that can be produced in the same facilities. When will we see old marine engines being repurposed to power data centers?

Now, let's shift our focus to comparing different solutions and manufacturers. We will also analyze the economics of on-site power generation and total ownership costs, comparing them with the U.S. grid.

On-Site Power Generation Economic Analysis

The key economic question for on-site power generation is: is its total ownership cost higher or lower compared to purchasing electricity from the grid?

Our analysis indicates that for the vast majority of data centers, on-site power generation is more expensive. In most parts of the U.S., the grid electricity price for large industrial users ranges from $40 to $80 per megawatt-hour. For newly constructed combined cycle gas turbine power plants, if their capital costs can be amortized over 20 years, the levelized cost of electricity can be as low as $40 to $55 per megawatt-hour (excluding transmission and distribution costs).

In contrast, the costs of on-site power generation are significantly higher:

- Modified turbines/industrial gas turbines: levelized cost of electricity is approximately $80 to $120 per megawatt-hour

- Piston Engine: The levelized cost of electricity is approximately $90 to $130 per megawatt-hour.

- Fuel Cell: The levelized cost of electricity is approximately $120 to $180 per megawatt-hour.

Key driving factors include:

High capital costs: The capital expenditure per kilowatt for on-site generator sets is typically two to three times that of utility-scale gas turbines.

Fuel costs: Although fuel costs themselves are roughly similar, the efficiency of on-site small units is generally lower than that of large combined cycle gas turbines, meaning more fuel is consumed per unit of electricity generated.

Operation and maintenance costs: The maintenance and operational costs of distributed generation units are higher, especially when they require frequent starts and stops or operate at low loads.

Redundancy costs: As mentioned above, overbuilding to match grid reliability significantly increases capital expenditures.

However, viewing on-site generation as a "more expensive" option may overlook its core value proposition: the time value. For AI workloads, the loss from delaying deployment by six months can reach billions of dollars. Therefore, even if the levelized cost of electricity for on-site generation is 50% higher, as long as it can be deployed months or even years earlier, its net present value may still be positive. This is why companies like xAI, OpenAI, and Crusoe are willing to pay a premium: they are buying time.

Equipment and Manufacturer Positioning

Based on our data center model tracking, our views on the market positioning of major players are as follows:

GEVernova: With its LM series aeroderivative turbines and HA class heavy-duty turbines, it occupies the high-end market. They benefit from brand recognition, a wide service network, and early success in rapid deployment solutions. However, they have the longest delivery times, which may push some demand to competitors.

Siemens Energy: Strong in industrial gas turbines and medium-sized aeroderivative turbines. Their SGT-800 is a popular choice in the data center sector. Similar to GE, they face extended delivery times but may respond more flexibly to medium-sized projects.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries: As a relatively late entrant to the data center field, they may gain market share through available capacity and aggressive pricing. Their J series turbines are highly efficient but have lower recognition in rapid deployment solutions.

Caterpillar/SolarTurbines: With the Titan and Saturn series industrial gas turbines, as well as modular, transportable solutions, they have become key players. They benefit from early collaboration with xAI and leasing models provided through partners like SolarisEnergyInfrastructure.

Wärtsilä: Dominates the medium-speed engine market and applies its maritime expertise to data centers. They provide reliable baseload power but have a slower ramp-up speed and are cautious about the operational complexities brought by large-scale deployment of numerous small units.

Jenbacher/INNIO Group: Leads in the high-speed engine sector, particularly through integration with VoltaGrid, offering "energy as a service" solutions. They are best suited for projects that require rapid deployment and operational flexibility Bloom Energy: Has a unique advantage in high-density urban areas or locations with strict environmental permits. Its deployment speed is the biggest selling point, but high costs limit widespread adoption. They need to prove their long-term reliability and reduce maintenance costs.

Boom Supersonic: A potential disruptor. If they can deliver the Superpower engine on schedule and achieve the promised hardware cost of $1,000 per kilowatt, they could capture a significant market share from existing manufacturers. However, they face execution risks and have not yet undergone large-scale validation.

Doosan Energy: As a new entrant in the H-class turbine market, they gained early attention with a large order from xAI. They need to establish a reliable service and maintenance network to earn long-term trust.

Future Outlook

On-site power generation is not a passing trend. We expect that before the large-scale upgrade of the U.S. power grid (which may take decades), on-site power generation will become an integral part of large AI data centers. In the coming years, we will see the following trends:

Hybrid systems becoming the norm: Data centers will combine on-site power generation, grid connections, and battery storage to optimize cost, reliability, and sustainability.

Fuel diversification: With the development of hydrogen and renewable natural gas supply chains, on-site generators may shift to low-carbon fuels to address environmental regulations and ESG pressures.

Standardization and modularization: Equipment suppliers will offer more pre-configured, containerized power generation solutions to further shorten deployment times.

Regulatory evolution: Air quality and emissions regulations will evolve, potentially providing fast-track permitting for on-site power generation using advanced emission control technologies.

The potential role of small modular reactors: In the long term, next-generation nuclear power may become an important source of on-site baseload power, but this may not occur until the late 2030s.

Ultimately, the endless demand for AI power is disrupting a century-old model of centralized power generation and transmission. The rise of "self-generating power" marks a shift in the power industry towards a more distributed, modular, and speed-prioritized paradigm. The grid may not "die," but it certainly needs to learn to coexist with these self-sufficient AI giants. A huge window of opportunity has opened for suppliers who can provide fast, reliable, and cost-competitive power generation solutions. The competition has just begun