How high will U.S. Treasury yields soar? Nomura: They may rise as high as 6% this year

野村表示,从长期的历史角度来看,10 年期美债收益率相对于 “CPI 通胀率” 和 “预算赤字” 这两个主要驱动因素而言仍然偏低:当前,经周期调整的 “CPI 通胀率 + 预算赤字(占 GDP 的比例)” 水平处于自 1960 年以来的最糟糕状态。

通胀顽固、赤字高企的背景下,美债收益率还能飙多高?

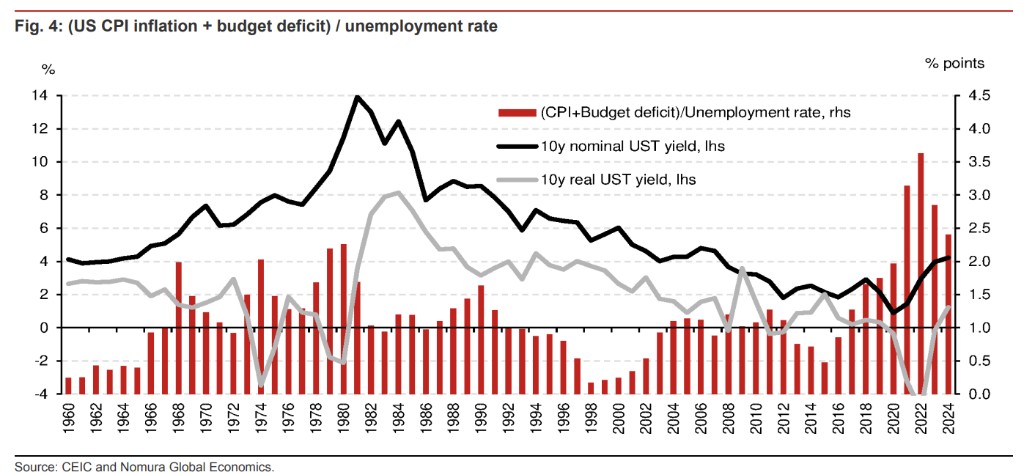

1 月 17 日,野村分析师 Rob Subbaraman 和 Yiru Chen 发布报告称,从长期的历史角度来看,10 年期美债收益率相对于 “CPI 通胀率” 和 “预算赤字” 这两个主要驱动因素而言仍然偏低。目前美债收益率应当参照 20 世纪 80 年代或 90 年代,而非过去二十年。

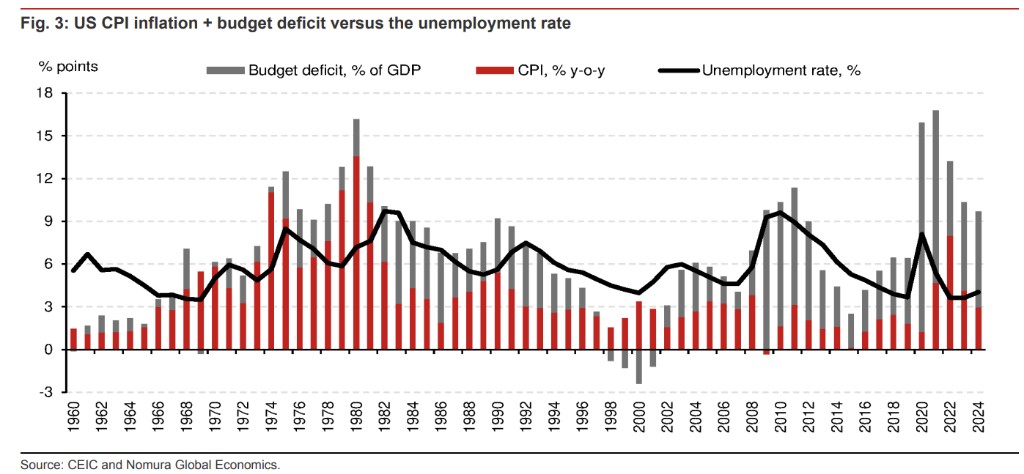

野村解释道,当前的 “CPI 通胀率 + 预算赤字(占 GDP 的比例)” 水平是 2011 年以来最糟糕的,但是,2011 年美国还未完全走出全球金融危机的阴影,失业率超过 9%,导致货币和财政政策极度宽松。

因此,如果根据经济周期调整(用失业率除以 “通胀率 + 预算赤字”),则结果显示:当前,经周期调整的 “通胀率 + 预算赤字” 水平是自 1960 年以来最糟糕的。

此外,野村还表示,特朗普政策可能进一步利用美国作为全球储备货币的优势,而这也可能导致 10 年期美债收益率继续上升。

然而,美国联邦政府削减预算赤字的空间很小,再加上到期债务的再融资需求,可能导致今年美债发行总量达到 GDP 的 17% 左右。

在大量低息债券到期之际,美债收益率上升直接提高了政府的净利息支出。此外,美联储的量化紧缩政策以及外汇储备的调整(要么降低美元配置,要么卖出美债以进行汇市干预)可能导致官方对美债的购买力度不如以前强劲。

综上所述,野村预计,10 年期美债收益率可能进一步飙升至 5-6%。

截止发稿,10 年期美债收益率报 4.6%。

1995-1996 年的情景重现

野村表示,10 年期美债收益率近期上升的最直接原因是美国经济的韧性以及 “最后一英里” 的通胀挑战,因为这限制了美联储进一步降息的空间,而这种经济背景与美国 1995-1996 年的情况类似。

当时,核心个人消费支出通胀率略高于 2% 的目标,但失业率略有上升,且联邦公开市场委员会的会议记录显示出对美国经济衰退的担忧。1995 年 7 月,美联储开始降息(从 6.00% 下调 25 个基点)。

尽管 5.75% 的实际政策利率依然较高,但美股市场表现强劲。最终,美联储仅在 1995 年 12 月和 1996 年 1 月分别降息了 25 基点,然后将利率维持在 5.25% 的水平长达 13 个月,并于 1997 年 3 月加息 25 个基点。